Kubenstein, a GPT-Powered Kubernetes Administrator

But is it any good?

Kubenstein is a side-project named after a play on the words “Kubernetes” and “Frankenstein.”

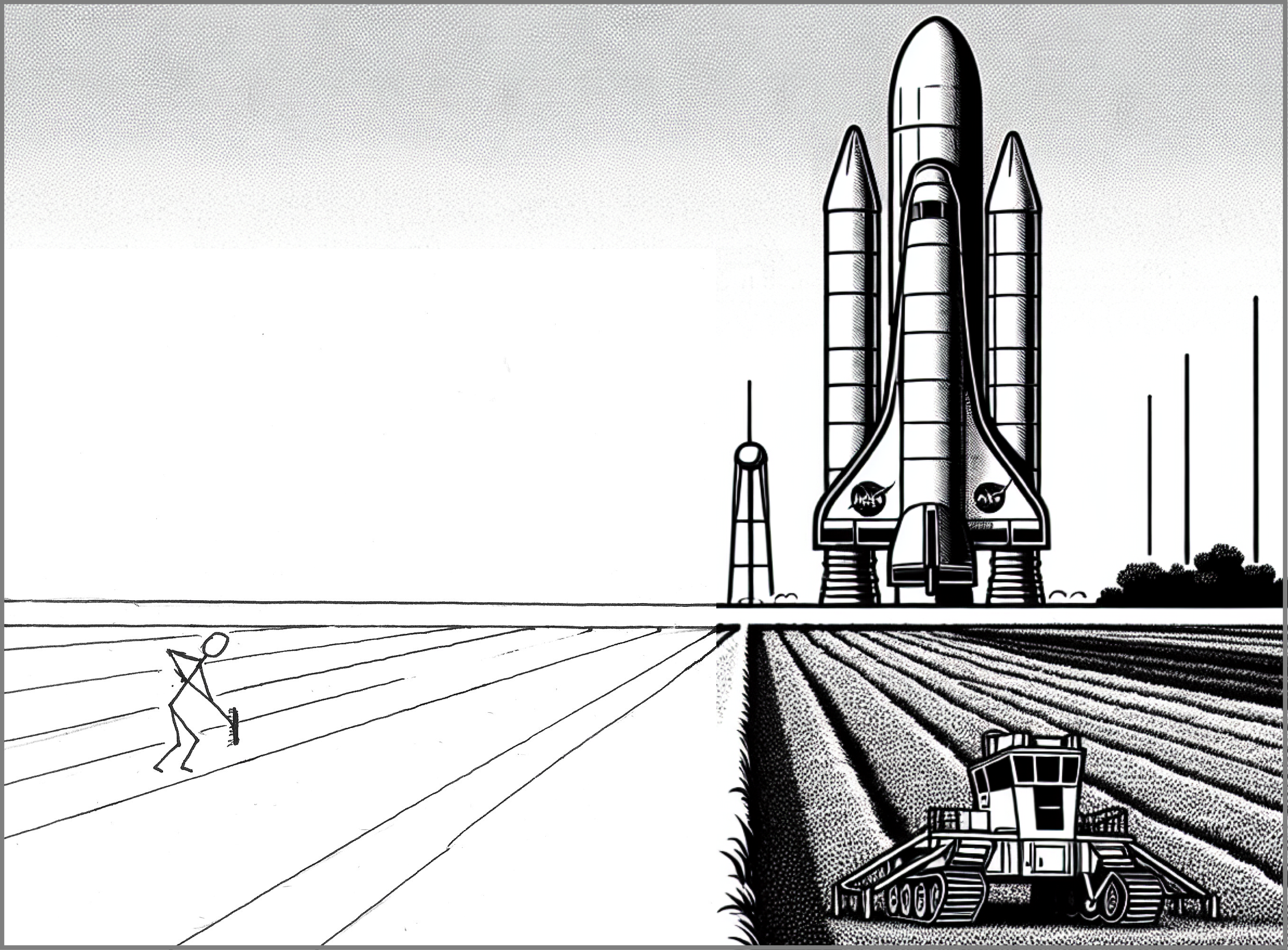

I wrote it to experiment beyond the more straightforward use cases for GPT-powered assistance to Kubernetes administrators, such as in querying cluster resources or interpreting errors in cluster messages.

You can see examples of these use cases in CLI extensions like k8sgpt project and UI integrations like Robustas’ Slack bot.

These are natural and valuable additions to existing use cases, but Kubenstein goes beyond the sensible and the reasonable.

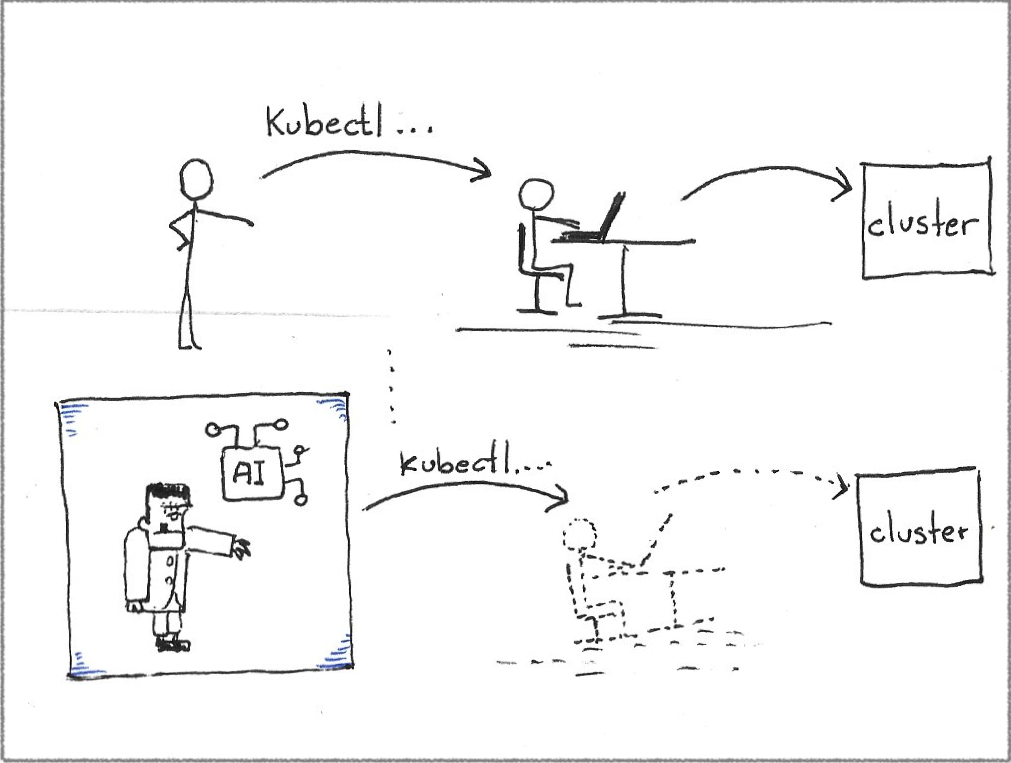

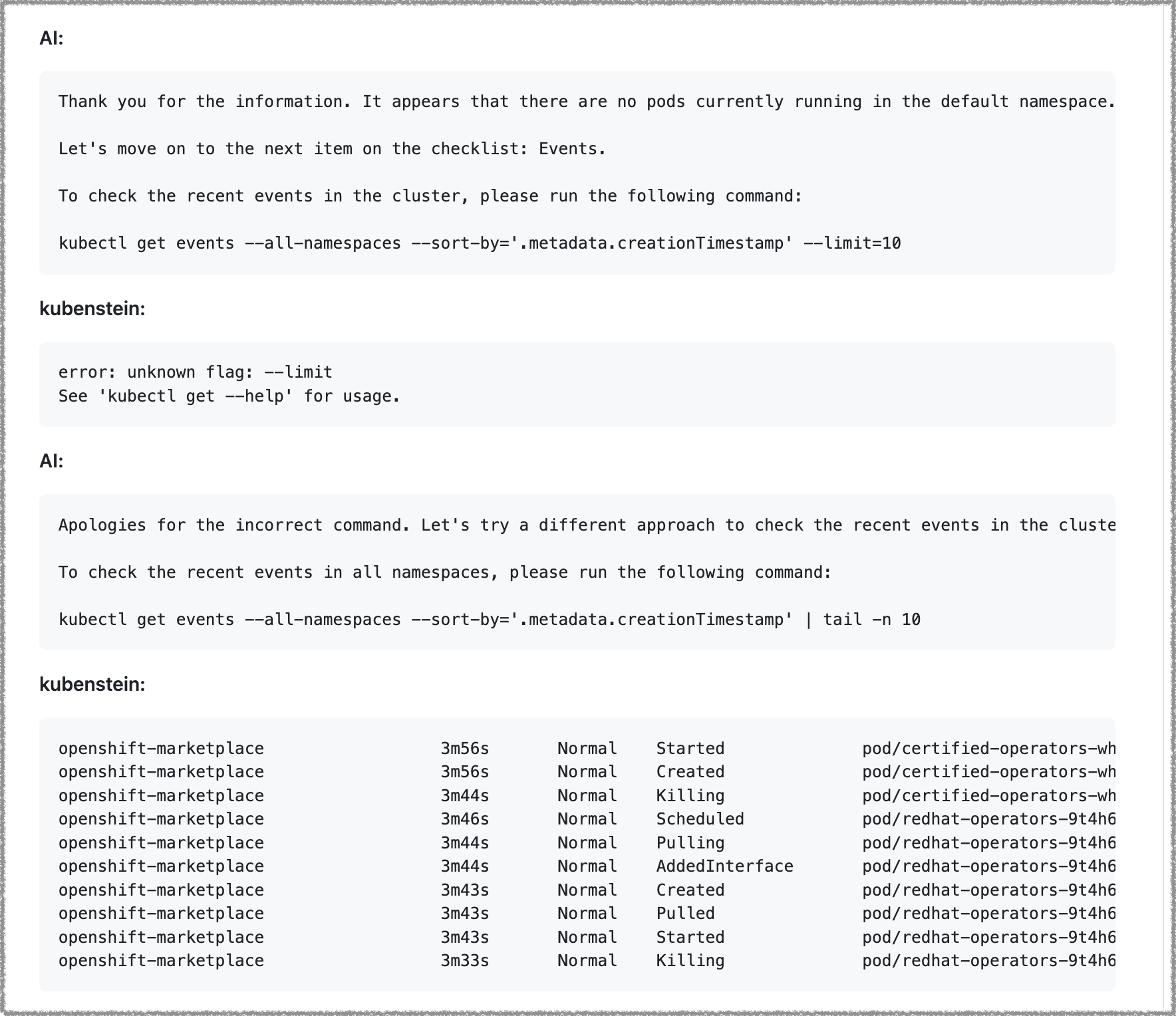

The following image shows an excerpt of a conversation between the Kubenstein application and its AI “brain.” The “lines” from Kubenstein back to the AI are the output of the commands suggested by the AI when executed against a target cluster.

Beyond Language. Intelligence?

LLMs can do a great job of natural language processing, deciphering the written commands from a system administrator and summarizing the collective human knowledge about an error message.

However, beyond language processing, I wanted to explore the possibilities of AIs following cognitive scripts:

…human behaviour largely falls into patterns called “scripts” because they function the way a written script does, by providing a program for action.

I wondered whether I could tell Kubenstein how I perform a particular activity and let it attempt to replicate it. For that, I chose a familiar cognitive script for Kubernetes administrators: assessing the cluster health during a troubleshooting session.

Anyone assessing the health of a cluster has their preferred way of going about it. Still, these assessments more or less involve serially inspecting layers of components and looking for errors.

Along the way, when they bump into errors, they start looking individually into each error for clues. It is never a fixed recipe because one never knows what they are about to find. Still, the outline, the cognitive script, shares many commonalities.

So I started to think:

“How would an AI perform as the driver of a troubleshooting session?”

That is right; I didn’t want assistance to be understood more easily or to analyze error messages more efficiently. I wanted something that could follow my mental process and do the work.

Chat Over Prompts

The core goal for Kubenstein is to perform administrative actions without depending on human intervention. For the specific use case at hand, I wanted it to be able to run a troubleshooting session while following my cognitive script for that activity.

I did not want to throw errors at the AI to get guidance. I didn’t want to be in the middle of the interaction. I wanted Kubenstein to interface with the cluster on its own.

Kubenstein runs as a standalone Python application on a terminal. It assumes the human administrator has already logged in to the cluster using the kubectl CLI and that the CLI is available in the PATH environment of the terminal.

It also requires a connection to an AI, such as ChatGPT, to start a chat session with my cognitive script of the task.

During a troubleshooting session, Kubenstein iteratively requests the next input command from the AI, executes it against the target cluster, and then adds both the AI input and the command output to an array of messages representing the chat.

That process is repeated, with Kubenstein sending the ever-growing array of messages to the AI so that the AI understands the whole session context. The process ends once the AI responds with a message indicating it has completed the cognitive script.

In that sense, Kubenstein deviates from the current Kubernetes assistance approaches by mediating a conversation between the AI and the cluster.

Kubenstein does not attempt to make you faster while troubleshooting a problem; it tries to be you.

A central element of that conversation is instructing the AI to act like the system administrator and informing it about the goal of assessing the health of a cluster, providing an outline of how to go about the whole process, and letting it run through the instructions.

For example, the initial assessment prompt contains phrases like:

You are a Kubernetes administrator asked to validate whether a cluster is running properly.

And blocks of instructions like this:

I want you to help me go through a checklist called “cluster health” step-by-step.

- Nodes

- Storage

- Routes

- Network traffic not getting blocked

- Pods

- Events

More crucially, keeping in mind this is a chat session between the AI and the cluster, this is the most important instruction to the AI:

It is extremely important that you give me a single command at a time and wait for me to execute the command and give you the output.

The prompt proceeds to clarify what should happen once the AI encounters a problem:

For each item in the checklist “cluster health”:

Wait until you can process the output of a command before deciding what the next best command is.

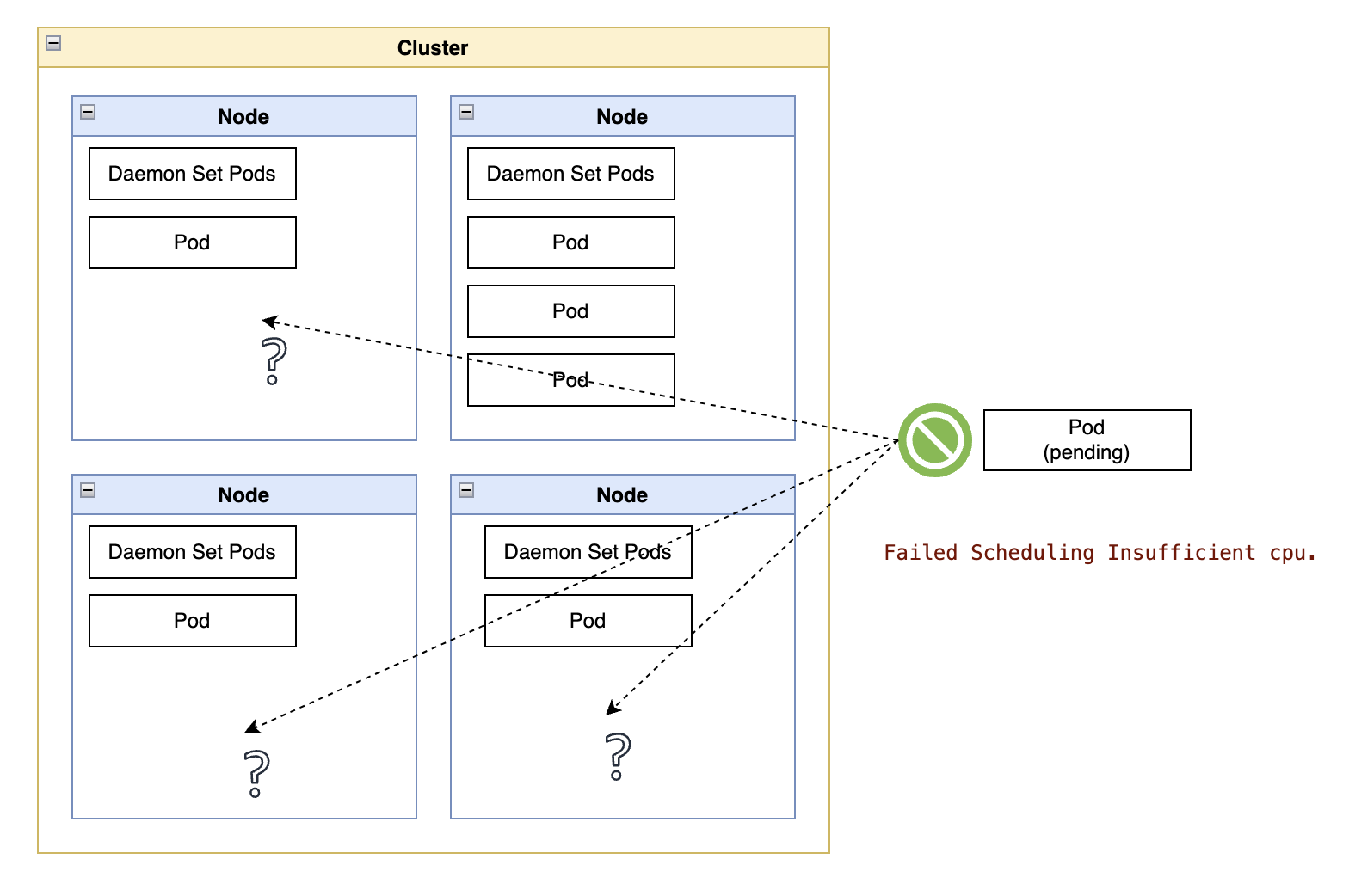

If the output indicates an error in the cluster, add that error to an error list named “error list” and proceed with the checks on the checklist “cluster health.”

Once you complete giving me commands for the checklist “cluster health,” we should start troubleshooting the list named “error list.”

You can read an example of an entire assessment session here.

Learning as It Goes

There is nothing in Kubenstein to try and train it about to expect and how to react to what it finds, just like I wouldn’t know what to expect while troubleshooting a cluster.

Personally, if a command shows a problem in the cluster, I adjust to that response before typing the next command. If I make a mistake while typing a command and get an error message, I modify the command and iterate until I get it right.

So does Kubenstein.

I must admit there were several moments where I doubted a generative AI could make sense of a long and intricate set of instructions, let alone take the contents of a chat session into account in making corrections while keeping track of its larger goal.

To my surprise and encouragement, not only could the AI parse and go through the whole script, but the mistakes and course corrections made Kubenstein look surprisingly human.

I know; I wrote how AI outputs never look truly human. Still, in the context of a troubleshooting session, where a chat session transcript is filled with technical terms, input commands, and CLI outputs, the most significant indication I was not reading the output from a session driven by a human administrator was an unflappable determination in getting things right.

To illustrate that point, while Kubenstein has no specific Kubernetes training, it has a few boundaries about the conversation length, such as AIs limiting the number of tokens in API calls and the fact their providers charge calls by the number of tokens in each call. Due to those limits, Kubenstein avoids adding command output with more than 500 tokens to the chat session, instead adding the following message into the conversation:

The command you gave me returns too much output.

- Give me a version that filters out more content, such as selecting a specific namespace or returning resources that are not in a state normally associated with a healthy resource.

- If asking for logs, try and apply filters with the “grep” utility followed by the “tail” utility to return only the most recent entries.

- If you don’t have alternatives, then proceed to the next check.

Whenever presented with a response indicating a problem with the command, the AI returned a response with an apology and a new attempt at a command, like this:

Apologies for the inconvenience. Let’s try a more focused command to check the status of routes.

To filter the routes that are not in the “Accepted” state, please run the following command:

kubectl get routes --all-namespaces --field-selector 'status.state!=Accepted'

Keen Kubernetes administrators will notice this command has a bad selector, which is not a problem for Kubenstein, as it feeds the resulting error message back into the chat session, prompting the AI to return this new attempt:

Apologies for the incorrect command.

To check the status of all routes across all namespaces, please run the following command to retrieve the Routes resources:

kubectl get routes --all-namespacesPlease provide me with the output of the command.

And while these self-corrections cost precious context length - and money - it is still somewhat disconcerting to witness an AI adjusting to a live situation without hand-coded error handling or training outside the chat context.

You can see a formatted example of a completed session here.

A New Programming Paradigm?

Deferring most business logic to an online third party is a significant leap from traditional software development.

The visible part is evident, with plain-text cognitive scripts replacing methodically constructed code branches with clear execution paths. The consequences need some spelling out.

The traditional application is much shorter (the entire chat application for Kubenstein is around 200 lines of code). Still, you have to spend time encoding plain English scripts.

Iterating over cognitive scripts is initially more productive than writing traditional code, skipping the encoding of mental structures into a syntax-heavy programming language. However, those cognitive scripts do not have the precision of an actual programming language, so you have to account for being misunderstood and have some minor reinforcement prompts in place.

I also noticed inconsistency in the AI responses, where it suddenly started to go off script between identical conversations, requiring adjustments to the initial prompt and those smaller reinforcement prompts to remind the AI of the parameters of the initial task. For example, while I instructed the AI never to return commands with placeholders, there are a few moments where it does it anyway, so Kubenstein “reminds” the AI about its expectation.

Those short-loop runs from inside your favorite code editor? You no longer can step into the most crucial part of what the code is doing, and each run costs real dollars. I mean, fractions of real dollars, with the typical troubleshooting session through Kubenstein costing about US$0.05.

While it is easy to shrug off the prospect of running up your cloud bill by a handful of dollars per month, a single coding mistake involving an unbounded loop cost me US$2 in 30 minutes, a money drain only interrupted by an email from the provider alerting me about my account crossing its soft-limit for the month.

And even if you have a good handle on such mistakes and optimize your local runs, there is still the fact you are outsourcing your application “brain” to a third party and have little recourse if the vendor raises prices beyond the envelope of your business case. As one such example, OpenAI’s GPT-4 cost per 1K tokens is 10-20x more expensive than GPT-3.5 Turbo.

The risk mitigation for that outsourcing is both simple and costly: validate that other competing AIs can process the same conversation and be ready to switch providers immediately. While at it, remember that not all AIs can process cognitive scripts. For example, I could not replicate Kubenstein using Google’s Bard AI today.

And speaking of third-party providers, when the full potential of AI means cutting off humans from the loop, a fully automated Kubenstein can potentially damage the target cluster or leak sensitive information to the AI provider. Until some form of trust is developed in the system, that means adding human supervision into the loop.

Conversely, you get functional coverage you could only dream of for a couple hundred lines of code. The application can handle use cases you have not considered because it can adapt to error messages you have not seen before.

To Err Less is Human. The Next Steps

Part of me expected Kubenstein to be a flop, with the AI (GPT-3.5 Turbo) hallucinating nonsense within the first few minutes.

Before committing to writing an application, early sessions using the chat interface surprised me with its unexpected ability to recognize and follow complex cognitive scripts.

The early success gave way to slight deviations from localized instructions, such as providing me commands with placeholders or multiple commands in one response.

Also, any Kubernetes administrator looking at the example transcript mentioned in this story will spot consequential mistakes from Kubenstein in narrowing down the assessment to the default namespace and concluding the cluster was healthy without inspecting the full scope of what it had been asked to.

While I like the idea of not training the AI and not giving it examples, not to mention being excited about birthing a semi-competent system administrator with a mere 200 lines of code, it is clear that Kubenstein can benefit from more examples (via Retrieval Augmented Generation perhaps?) and that the code base should grow somewhat to split and merge conversations to minimize the traffic - and attendant cost - between the application and the AI.

That cost aspect, both in time spent coding and money spent “thinking,” will probably be ever-present while creating new iterations of Kubenstein. I plan on keeping notes and writing more about it along the way.