Rewriting the Most Critical System in the World

But first, we need to go back to the source

Software development is a continuous process of creating abstract new worlds, a topic I covered in “What Is the Hardest Thing in Software Development?”

With so much of that process’ success hinging on the ability to construct knowledge from sensory information — learn — and share that knowledge with others — educate — it is surprising that we rarely stop to reflect on our ability to do those things well.

Many of us tend to see learning and education as secondary skills to a seemingly core skill of encoding knowledge into artifacts (design and programming.) Over time, we get better at these “soft” skills without realizing we just rounded out the bare minimum to create software effectively.

As you read through this story, consider a few common scenarios experienced in a student role:

- Trying to fit in as the new member of a team that has been together for a while, learning their existing product and code base.

- Studying additions to the system made by a colleague before making comments on a design document or pull request.

- Finding information about a new feature in a system (real world or virtual) and the best scenarios to use it.

Conversely, consider the opposite side of some of those scenarios as an educator:

- Supporting the onboarding experiences for a new colleague, such as writing an introductory presentation and choosing their first tasks.

- Explaining additions to the system to a colleague or stakeholder, either informally or through a series of presentations.

- Preparing a presentation of a new topic for a conference or to your local team.

These are not scenarios that we only encounter later in our careers. They are day-1 activities often met with haphazard preparation and delivery, negatively affecting the work environment and business results from the beginning.

More insidiously, the lack of mental schemas in education is often paired with copious amounts of naïve realism, raising software developers with insular attitudes towards customers (“the users don’t get it.”) and collaborators alike (“the technical writers can’t keep up.”)

As software developers, we are used to continuously improving systems and fixing minor defects in the next system iteration. But when the issues affect the building pipeline itself, it is time to stop everything and fix the problem.

The system of genesis

Before fixing a system, we must first understand its rules and how it works.

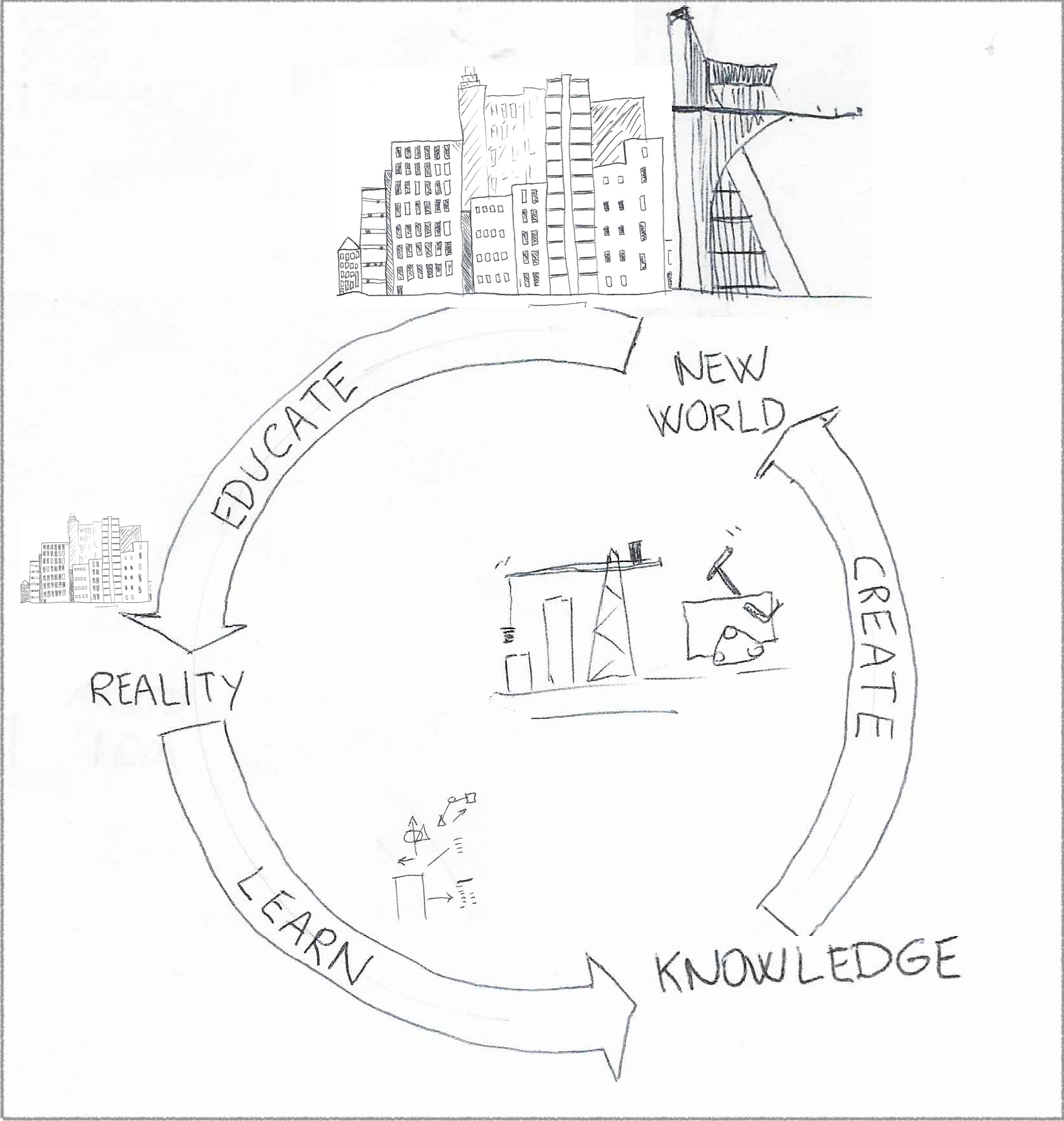

When we look at the process of creating new worlds — or, more accurately, augmenting existing worlds — we find three activities that happen more or less in this order — at least in each iteration of the process:

- Learn: Software systems must fit into larger systems, so we need to learn what matters most about these larger systems — and picking what matters most is also part of learning.

- Create: Collaborate with colleagues and stakeholders of the existing system to augment it, creating a new one in the process.

- Educate: This activity splits into colleagues educating one another about their contributions to the system and then educating users about changes to existing concepts, relationships, and workflows.

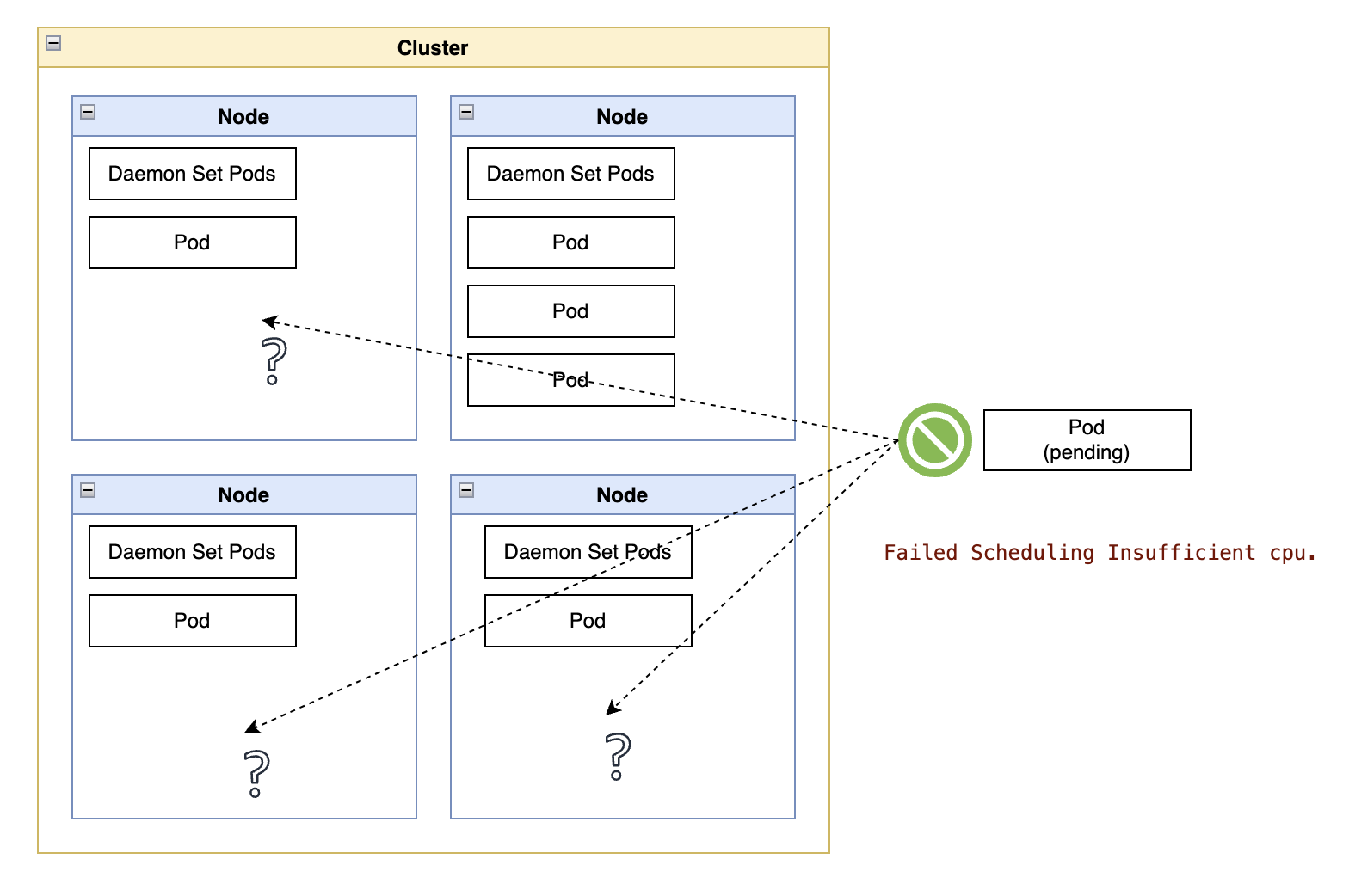

These three activities exist — with different names — across all mainstream software development processes. Get all three right with a half-decent business case, and success is all but guaranteed. Bungle any of the three, and then failure is guaranteed.

Even if not completely failing at one of those activities, missteps and improvisation in the learning portion have a compounding effect throughout the entire product lifecycle, setting an increasingly lower cap on customer satisfaction.

Conversely, every slip in sharing knowledge means users cannot engage parts of the product, erasing large chunks of its value.

Outside learning and education, when we look deeper into failures of execution, they invariably trace back to a form of “not knowing” [something] or “not communicating” [what we know to others.]

Now that we know what matters in the system, it is time to revisit the past and reforge some critical tools.

Studying (in) one of the largest systems in the world

Whether we recently graduated or have been in the field for a while, no matter how much knowledge we may have, our learning and teaching skills trace their roots to one of the world’s most well-established and formalized systems in the world: the school system.

Those influences manifest at the surface of our interactions but originate at the core, close to fundamental mental schemas formed in the past.

It is time to start some of that rewriting mentioned in the title of this story.

Two doctrines to leave behind…

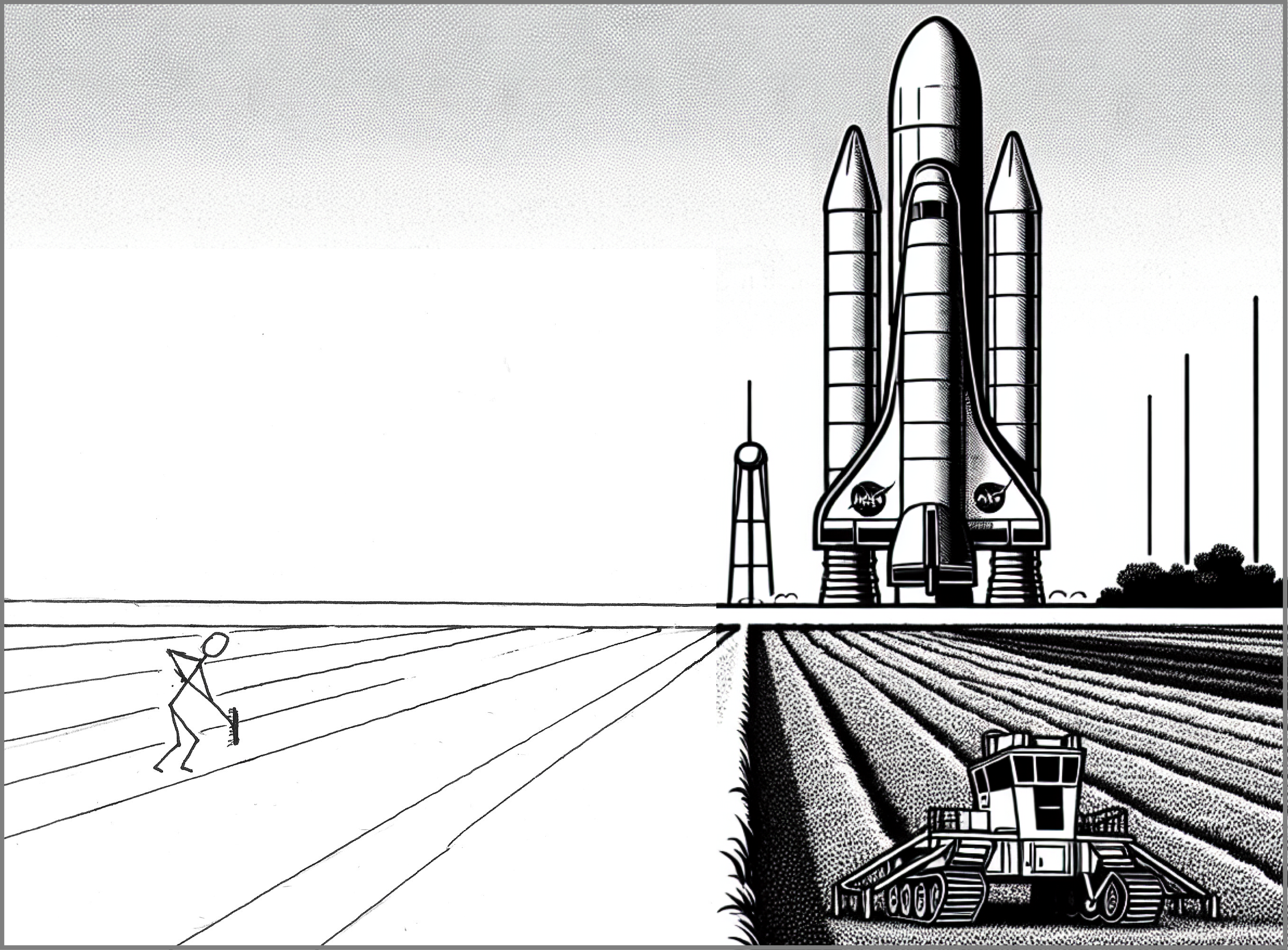

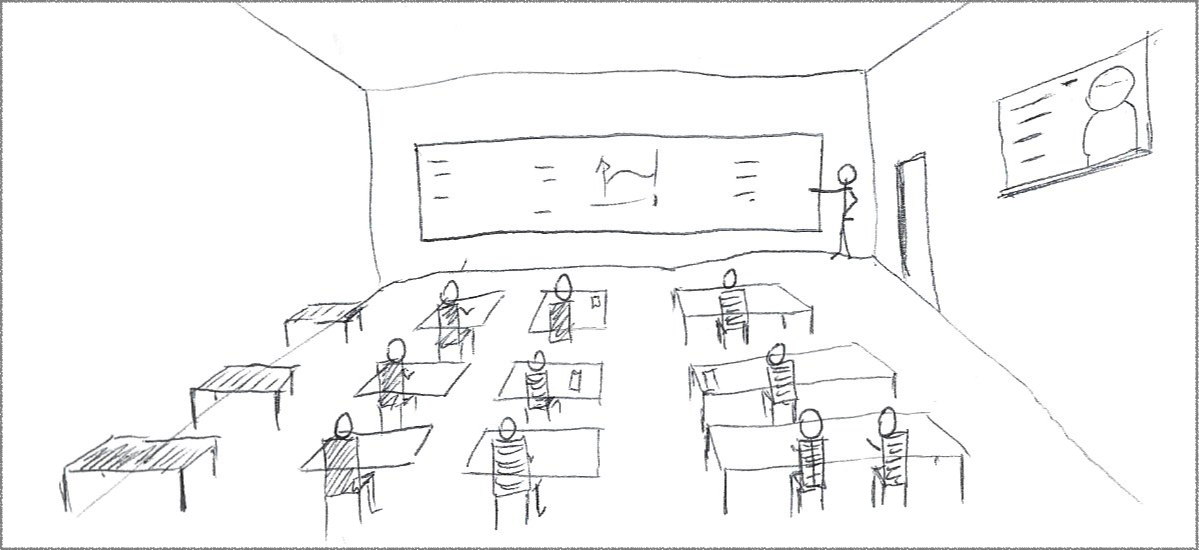

As a system, school is a mass-production pipeline spanning 10 to 14 years of education, extending by another 3 to 6 years for a college degree. It is a structured environment bringing teachers and students into classrooms on a fixed calendar schedule. As with any system, it breaks down into a complex combination of parts, participants, and workflows.

A factory of knowledge for the factories, based on a model with roots going back to the Prussian education system of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Its derivations continue to this date, anchored in compulsory attendance and disciplined delivery of instructions.

Functioning in a school system requires quite a bit of malleability, especially for young students without prior experience in judging its parts. Give it enough time — and anything over a decade is plenty of time — and it can be really hard to negotiate a path through the system without becoming a part of it.

I could write a long list of undesirable mental models picked up along that journey, and I think this list may shift on generational boundaries, but here are two lessons we need to leave behind:

Doctrine #1 — Knowledge is handed from a desk. In the adult world, anyone with knowledge can share it. Add the power of stories, remove the need for fixed delivery schedules, and people with as little as an hour of free time to learn a few techniques can become better educators by the end of the day.

That desk out front is also a symbol of justice and knowledge rolled into a single entity, mixing faculty and staff. Those two attributes may correlate but often walk separate paths. It is easy to form an incorrect association for life when we are young adults without good mental schemas for those two concepts.

Doctrine #2 — Challenges (tests and assessments) end on a deadline, regardless of results. Once again, remove the requirement for fixed delivery of curriculums and fixed deadlines for exams, and we are left with a new world of possibilities.

A few years ago, as an assistant coach to a youth soccer team, I told a struggling goalkeeper about approaching each play expecting the contact with the ball to be only the first of many. I capped the lesson with, “The play ends when the ref blows the whistle, the ball is behind the line, or in your [team’s] possession.”

Starting on the next game, he was transformed. He still struggled with first-time saves but replaced startled reactions with immediate follow-through to secure the ball or get it out of the field.

…and three passions to rescue

As we become part of the system, we start to mix our dislike of the system with a dislike for the things the system touched upon, whether in the delivery of information or in the discipline required to process that information on fixed schedules.

And because we never stop to examine the difference, we tune out of the whole thing once we leave school.

Here are my top three things to bring back from the past:

Passion #1 — Learning. Learning is an irreproducible skill, at least at the generalized levels of human ability. It is the second most valuable privilege in society — behind life itself. Never outsource it.

During school, we often questioned the value of the information we were given. We often could not see the future adult world where some of that information would be useful. Even today, high schoolers going through a lot must wonder why they should spend time writing when an AI can often do a seemingly better job — that is another topic for another day.

Many of us may have momentarily or permanently lost the love of learning because we felt too much of the information would never be helpful. However, it was never about the facts; it was about learning to learn.

Passion #2 — Fearlessness. As our hunting and gathering ancestors could tell us, challenges ended when the job was done, and the job only ended in two ways, one of them good.

Fear is a healthy self-preservation instinct when planning but often a fatal distraction during execution. As children who often did memorable — and stupid — things, we instinctively knew that. Remember the exact moment when you committed to a run or lit the match that marked the start of an improvised science experiment?

Once you commit to a decision, start everything with that same feeling.

Passion #3 — Educating is a privilege and responsibility

As students, we trust someone with the formation of mental schemas that will govern our future actions. We may forget the information, but we never forget the experience.

When we inform, coach, or mentor someone, more than handing out facts and guidance, we are helping people form perceptions of the world.

When we hear our technical elders talk about communication skills, listening, collaboration, adaptability, empathy, and patience, they are urging us to develop the qualities of being a good teacher.

A good or bad experience today will spider through a web of relationships for multiple generations, leading us to the next section.

System theory and the theories behind the system

When learning and educating are integral parts of the profession, that professional field is an extension of the education system. We keep learning and educating in the same ways we observed for most of our lives at that point.

When we consider that professional educators may carry some experiences from their learning years into the classroom, it is not uncommon for professionals to practice educational skills from 40–60 years ago.

On the learning side, how often did we find ourselves waiting for information from a colleague when individual research could yield more knowledge? On the training side, how many of us have reflexively lined rows of desks in a training facility to dispense an improvised curriculum from a desk out front?

With the pipeline of educational theory (and methods) lagging to the point where we risk retiring before those improvements reach us, it is a good idea to take a stroll up the production line and maybe pick out some exciting building blocks that may be a decade or two away from reaching our current position.

As we walk up that production line, we find theories in reverse chronological order, with the oldest ones first (the ones we are practicing now) and the recent ones last (the ones we may never get to practice.)

There are many learning theories, but we went through a system heavily based on “behaviorist” and “cognitive psychology” learning theories. These are the two most prominent learning theories, with “constructivism” rounding out a de-facto triad — chime in the comments section if you spot your school having used something outside these three.

Behaviorism

As the name suggests, behaviorists are interested in measurable behavioral changes, dealing in terms like classical conditioning and its better sibling, operant conditioning.

Classical conditioning is about unconsciously pairing specific actions or stimuli with a behavioral response. If classical conditioning sounds cynical and inadequate as an educational tool, that is because it is.

Operant conditioning employs positive and negative reinforcements to encourage or discourage behaviors. Ask different generations about the benefits (or necessity of) negative reinforcement, and you get different opinions. That does not make older generations necessarily meaner. Still, they spent a good part of their formative years being conditioned to follow the rules, even those we may consider excessive or abusive in the present.

We can fight monsters without becoming one, but it is a lifelong battle in a front between flexibility and order, constantly worrying that one may overtake the other. One must fight monsters with care.

Positive reinforcement is the only salvageable branch of behaviorist theory. There are great examples, such as praise, a high five, and telling someone we are happy for (or fond of) their accomplishments.

I conclude with an acknowledgment of its corporate offshoot: gamification. There are good and not-so-good implementations. The overarching theme for successful ones is a system that benefits the employee or things the employee cares about. On the flip side, naked PLB strategies (Points and Leader Boards) generate a rush of initial enthusiasm and eventually fail to sustain engagement. Net: Save the Dopamine rush strategies for online games.

Cognitive psychology

Cognitive psychology started to make inroads into learning circles around the late 1950s. The class of school teachers influenced by those theories would take a generation to reach classrooms.

With cognitive psychology, educators start discussing subjects such as perception, language, metacognition, and knowledge organization.

People begin to consider neuroscience to weigh on curriculum development, correlating cognitive function with their physical location in the brain. Common knowledge (“taking a walk helps me think”) becomes science (“people perform better on tests of memory and attention after brief physical activity.”)

We start to learn how we learn, with life-changing impacts. As a small yet powerful example, cognitive sciences dissected the mental processes behind attention and perception in learning, showing how sensory processes occur independently of reasoning. As a result, the education system started accommodating the concept of learning disabilities. Suddenly, students destined to fail the old system begin to succeed with simple accommodations, such as access to written lecture notes ahead of class and extended time to take tests.

We start to examine and map out the awareness of thought processes and how they work, forming the discipline of metacognition. For example, when we spot an 18-foot tall stick with a green mass on its top, our brains invoke the mental schema of a tree. Being aware that our brain is executing that process is an act of metacognition.

More than fighting monsters, education leaders started to believe they could win.

Constructivism

Around the same time the Prussian education method spread worldwide, Dr. Maria Montessori’s work showed that children left to their own devices with limited guidance could outperform others in public school.

That work inspired and shaped the ideas of Jean Piaget, who served as the head of the Swiss Montessori Society for many years. Piaget went on to form the theory of cognitive development, putting mental models ahead of knowledge acquisition.

“From thought to structures, from structures to thought.”

I heard this phrase while in college decades ago. I tried to search for the author multiple times without success, but it is a powerful lesson nonetheless, as it describes the iterative nature of the cognition process.

We generate thoughts as we perceive the world. We process thoughts based on our immediate mental schemas. From thought to structures.

Experience and interaction with the environment may not fit the mental schemas, so we form new ones to help us make sense of the information. From structures to thought.

Now, fast-forward past formal education, and consider a constructivist approach in a professional environment, where smaller teams set their schedules and trained programmers can access all knowledge in the world at their fingertips. It is a perfect fit.

Here are the core concepts behind constructivism:

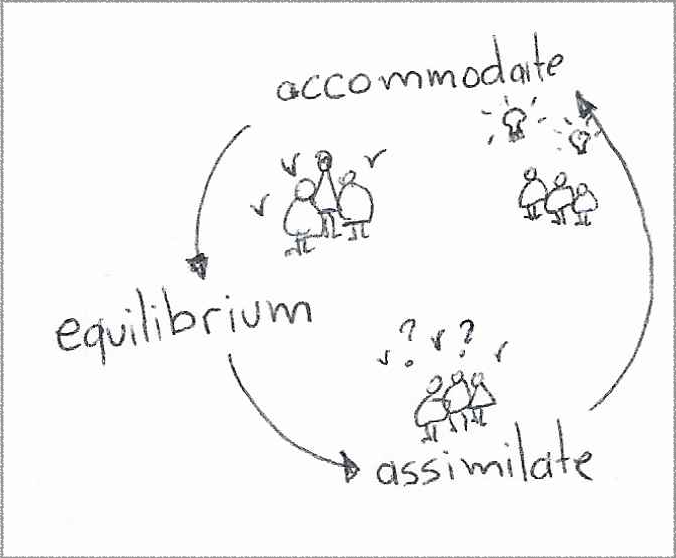

- Our minds are in perpetual pursuit of cognitive equilibrium:

- We assimilate the information from our environment according to our mental schemas. That is how we perceive the world.

- We accommodate information if we cannot assimilate it by modifying our mental schemas. That is how we learn.

That learning cycle may differ for software development because we often aim to modify the environment while interacting with it. Sometimes we create the entire environment in the form of virtual worlds themselves.

We can also see clear signs of constructivist learning in software development approaches like throwaway prototyping or iterative development. Each iteration is an expression of the assimilation phase, and we can only form the next set of improved mental schemas (accommodation) once we interact with the current version of the product.

Without a viable path in learning theory, the monsters drifted to the next stage of the system, leading us to the following section.

Going to production, from theory to practice

Once outside the school system, it is time to adapt learning theories to practices in a new system: the job market system.

We leave a structured approach of prepared curriculums delivered to us on a staggered schedule and join a world of ad-hoc onboarding and training processes.

As adults, we start favoring problem-centered, self-paced learning strategies focusing on what we consider relevant and urgent. The industry and educators are happy to respond with new theories and methods focused on increased productivity.

And what is more efficient in the short term than good-old behaviorism? What could be less constructivist and adapted to human learning than waterfall development processes reigning supreme until the early 2000s?

As software developers with an active role in transforming information into knowledge and communicating that knowledge, learning about educational theories and methods is not only part of the job; it allows us to see what others cannot.

At this point, I could start stringing descriptions of theories such as Andragogy, Heutagogy, and Expectancy-Value Theory. I could start weaving an argument about adopting aspects of Instructional Design in onboarding processes. However, I leave all of that for another day. I wanted to dedicate my final point of this story to the system in the title of this story, the most important of all.

You.

The brain and the mind form an incredible system. If the brain is the machine, the mind is a mixture of software and something else we still don’t understand: consciousness.

While we must leave the incomprehensible to philosophers and future generations of scientists, we should still learn more about the part we can explain.

We can go through life without examining our mental processes, just like we can use a smartphone without seeing the magic behind the glass. The problem is that, unlike smartphones, our brains and minds have been losing an invisible contest with reality.

That is why I suggest two crucial and very personal system rewrites before I offer my parting thoughts.

Schemas: The temple of you

If you have time for one thing after reading this story, watch “The Psychology of Schemas: Why Childhood Can Mess Us Up” by Dr. Tori Olds. It talks about the influence of parents, but you can extrapolate the effects to any adult figure in a position of influencing your childhood, like grade-school teachers.

As constructivist animals, processing information differently according to our mental schemas, we did not have as many mental schemas early in our lives. At the core of our present-day mind, we may still find the primordial schemas that processed our first rounds of information and the improved ones that accommodated that information.

We reason today with mental structures from yesterday.

In many ways, our mental schemas are like cathedrals built over several distinct periods, with different styles adopted across different ages. What we learned two decades ago influences how we will teach today, just like our teachers in the past taught with influences from how they learned even further back in time.

Understanding and recognizing mental schemas helps us deal with the past.

Biases: A crude weapon, for a less civilized age

If you have time to read a second thing after learning about schemas in the previous section, skim this list of cognitive biases.

Our brains and mind are highly adaptable, and natural selection contributes too. Still, science tells us the brain’s machinery is evolving at a much slower pace than our access to information.

Faced with new information, our brain mechanically approaches information and situations as something it may have seen before, attempting to make a decision similar to the previous one. That is a process called the heuristic technique. At some point in humanity’s distant path, that was probably the difference between being lunch or living to hunt another day. In modern times, it may be the difference between working late or eating dinner at home.

The modern challenge for heuristics is that it is a process adapted to small amounts of abstract information — indeed, a tool for a simpler time. When confronted with large volumes of nuanced information, we get the less desirable effect of biases, where our overwhelmed brain hastily misclassifies the information and generates an incorrect interpretation. Add aspects of social isolation and the attendant lack of signals pointing at a wrong conclusion, and biases can last a long time.

Understanding biases helps you keep your involuntary brain processes in check. It takes care of the present.

Parting thoughts

As you set out to create new worlds, you are in a unique position as the source of knowledge about those worlds. You are also uniquely positioned to learn what people need most from these worlds.

At the same time, we are conditioned from a very young age to receive information in ways that stifle creativity in favor of discipline and accept that people with formal titles have a monopoly (and responsibility) on educating others.

We cannot go back in time, but we can revisit the past. And in doing so, we can reconstruct mental schemas and develop (or strengthen) the conviction about learning and educating being foundational skills not only in our profession but also in our lives and communities.

And while all this is serious business and it is serious for business, it is also about rescuing our inner child in the process.