Three Steps to Solve All Your Problems in Tech

Where Clarity Leads, Solutions Find Their Way

We can describe most problems as “Something is not working like it should.”

When things don’t work as expected, it is time to practice some form of problem-solving. For example, if we want to restore a system to a running state, we can try methods such as Root cause analysis or Five Whys. If the problem involves challenging requirements while developing a new product, we may favor an exploratory method such as Design Thinking.

And when it all fails and a problem exceeds our skills and resources, it may be time for the well-known problem-solving method of help-seeking.

Asking for help is a familiar routine in a virtual world with an infinite supply of “somethings” that can fail or misbehave at any time, creating familiar challenges all around:

- Ask for help too early, and you risk wasting someone else’s time.

- Ask for help too late, and you risk missing an important delivery date.

It is in between those extremes that most organizations struggle to find balance.

Recognizing when to seek help and how to be ready to receive that help is the foundation of the help-seeking social contract, minimizing wasted time and maximizing collective progress.

Sometimes, It Does Hurt to Ask

One may argue that when the delivery dates are slipping or the SLA service credits are flying out of the window, it is always time to seek help. Right?

Not quite. We need to do some homework first.

Here is an example:

Developer: “@channel My nginx server isn’t working. What could it be?”

Slack UI: “Uh, Chief, do you really want to alert 3284 people across 11 timezones?”

Developer: “Yes, Mr. Bot. This is the darkest hour. Wake them up. The whole lot.” <clicks “Send”>

Twelve replies into a hailstorm of reprimands and lectures from the channel constabulary, someone finally breaks through the virtual mob: “Is it accepting connections?”

The hapless developer answers “No,” confused by the question’s relevance because “I already said it isn’t working!” He awaits what must surely be a final solution in the following answer, but nothing happens. The helpful bystander is seemingly gone for the day. But fret not; the developer messages his local senior developer and repeats the original question.

With all forward momentum converted into heat, wear, and tear, the developer awaits the rescue. Sitting by the side of the virtual road - a terrible place to be - the developer rationalizes his situation, reminiscing about the advice received earlier in his career:

- “Don’t spend too much time on it. If you get stuck for more than an hour, reach out.”

- “Don’t be afraid to ask for help. We are here to support each other.”

Those are unquestionable truths, but they are of the guardrail kind. They focus on what should not happen but don’t guide people on how much time is too much nor set the bar for a question being perceived as too basic.

What our hypothetical-but-all-too-real developer needs are clear expectations and usable guidance that make problem resolution more accessible and attainable.

That is this story’s topic, divided into three simple steps.

Step #1: Trust the Crowd. The Answers Are Out There

There was a time when the developers building the product or the system were the only source of information.

Getting things to work was challenging enough, and making documents user or task-friendly was an afterthought. Access to other users was limited, as was the access to the product’s source code. Finding information about the system and existing problems was protracted and meticulous work.

That was a long time ago.

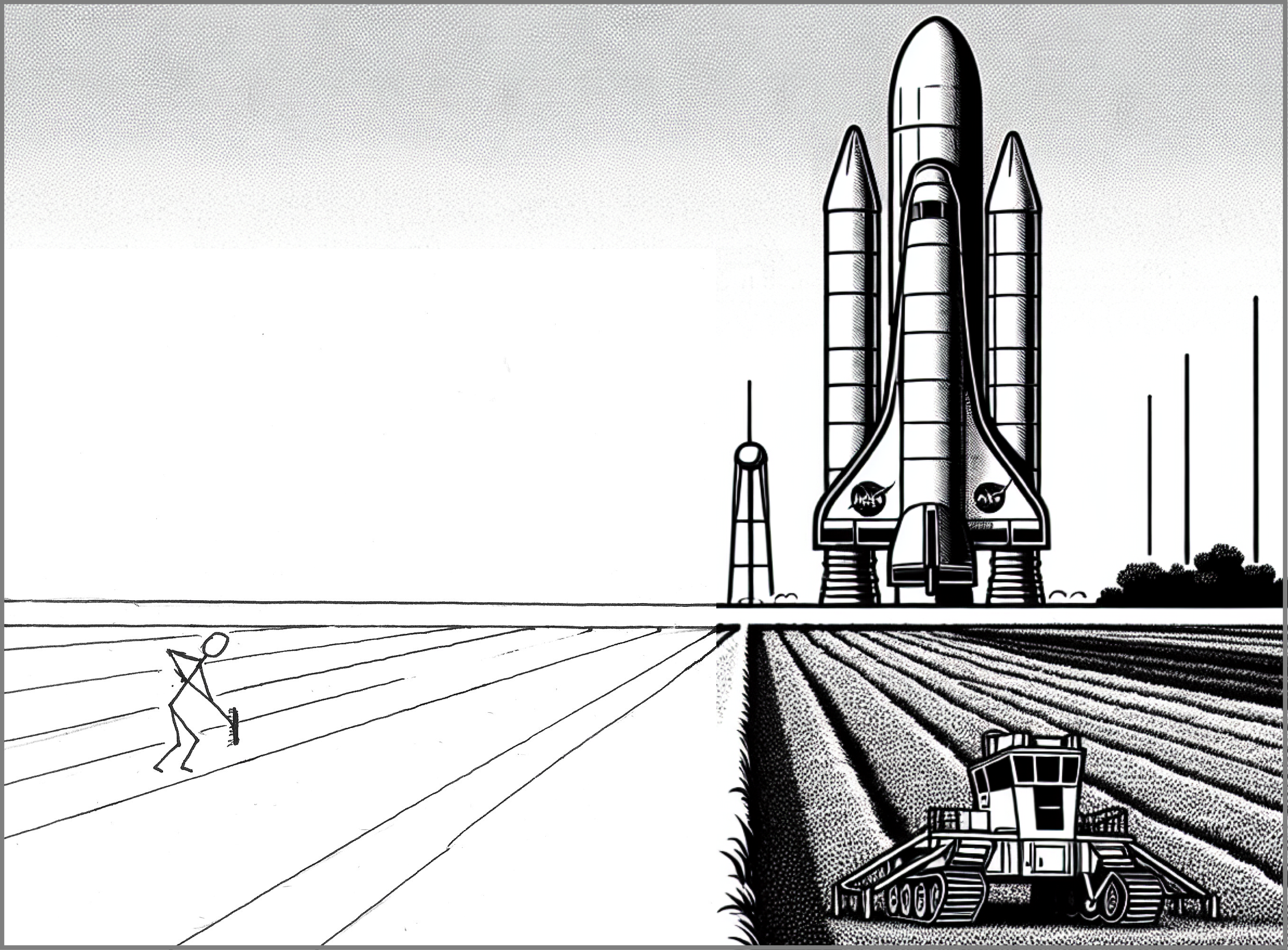

Except for bespoke systems built in-house by a handful of people, everything else nowadays is behind well-documented service APIs or available as open-sourced code. Access to information about products, libraries, and services in a modern Cloud environment is a solved problem. We can always gripe about some blind spot here and there, but the junior engineer of today is two web searches away from being more effective in solving their problems than a senior engineer of twenty years ago.

Beyond factual information answering simple “what is” and “where can I find” questions, public forums are treasure troves of information.

For all the complaints about the toxicity in web forums, muscle through the noise and you can find threads filled with valuable discussions. There, you will discover seemingly random people who post the correct answers to questions and debate the nuances of why incorrect answers are wrong and the range of situations where solutions will work. Hang around the comments section for an extra moment or two, and you can pick up on many other clues and related links to help solve the problem.

AI-powered bots like ChatGPT can also answer questions. However, I think the sanitized format of the answers does not offer the same rich learning experience of following one’s nose through web search results. After all, isolating positive signals from background noise is an invaluable problem-identification skill.

Step #2: Keep Moving. Help Will Follow

In nature, being stuck is a precursor to death. Conversely, in the virtual world, being stuck is a precursor to virtual death.

Lack of progress is depressing and demoralizing. It kills the spirit instead of the body. Yielding control over your progress to someone who can help restore that progress is a last resort to be used sparingly.

I am not writing this to shame people into not asking for help, but there are ways of asking for help without stopping while waiting for help.

“What if I really don’t know what to do? Should I be afraid to ask for help?”

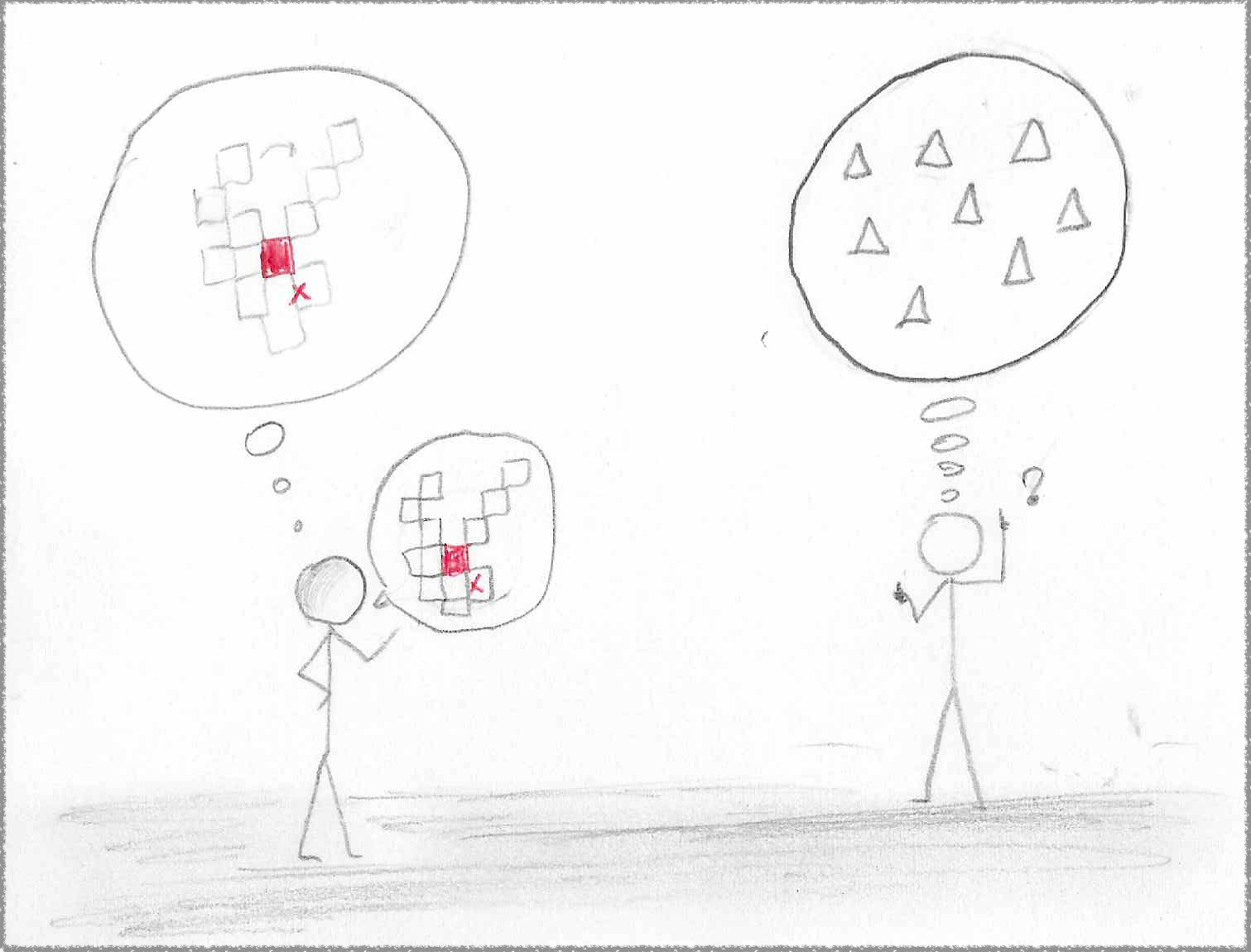

No, you shouldn’t be afraid. The time to ask for help may come and will be covered in the next section, but you probably can do a couple more things to keep moving. How many times have you asked a question only to think of the answer a minute later? That is your brain working through the intricate lattices of semantic networks and spreading activation.

As you shift your focus from solving the problem to describing the problem, your brain fetches different schemas to convey the information from a different angle. Those different perspectives often give you a clear line of sight to to the problem’s resolution.

“So, should I ask my question or not?”

While you can keep the problem in your head talking to a Feynman’s rubber duck, having access to a large team channel or Internet forum offers a powerful alternative: sharing the problem and working steps with others while you are still trying to solve the issue.

To quote comedian and philosopher Chris Rock:

“I used to have horrible cars that would always end up broken down on the highway. When I tried to flag someone down, nobody stopped. But if I pushed my own car, other drivers would get out and push with me. If you want help, help yourself.”

You can bring that lesson to software development and systems operations by framing your problem in a public thread like this:

“Hey, I am seeing the error message “XYZ” in this system. I am still working through it and will be posting my findings as a thread. Chime in if you have seen this message.”

Assuming you took the first step to heart and the solution to your problem is not the first result of a web search, starting such a thread in plain view of channel participants brings in multiple benefits:

- You can keep moving because you have not yet exhausted your resources and options.

- People can help you in their own time, so you are not interrupting their flow.

- Other people interested in the topic can follow the thread.

- Reframing the problem as something that can be shared with others can help you solve the problem

If later you find the solution and the question is not too basic after all, then you can post the answer and other people hitting that problem in the future can find a ready-made solution.

With this step, you are not flagging cars down the road; you are stopping to help others push their broken cars. And because this is a virtual world with little distinction between footprints and the body leaving them behind, you may be helping others without knowing.

Personally, I am somewhat spoiled by working in a large company with large Slack channels. My searches in our internal workspaces turn up a helpful answer 95% of the time when I hit a new problem. They turn up a working solution in almost 80% of the cases. And for the remaining 20%, taking the failed search to the Internet brings the search-to-solution ratio to almost 100%.

One can still be highly dependent on others to complete their work, but one doesn’t need to be blocked waiting for help.

If you worked through the first two steps and still haven’t found a solution, it is time to ask someone to commit their time and resources to assist with the resolution. The following section shows how one can maximize their odds and minimize their losses (of time) by gathering a few facts ahead of time.

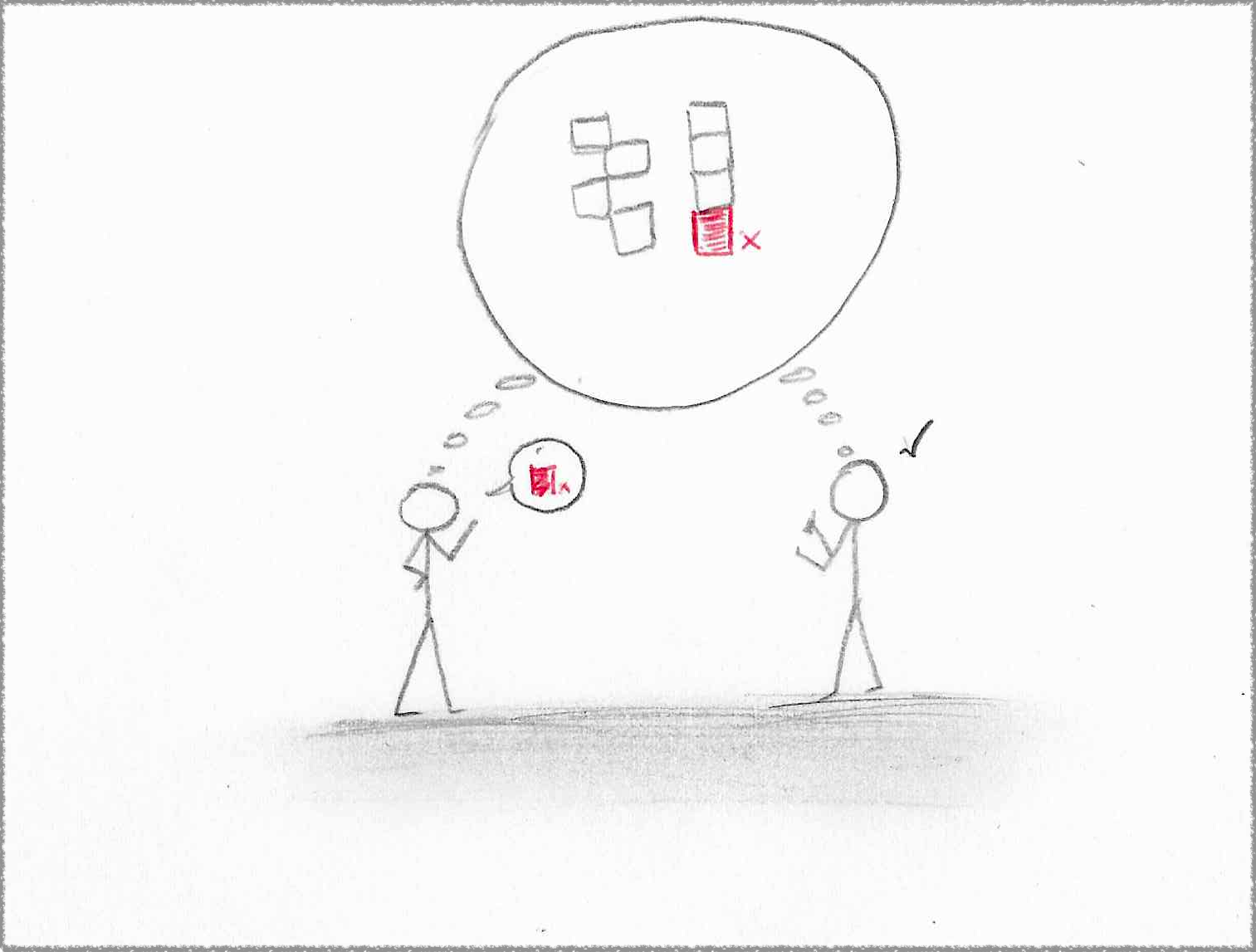

Step #3: Gather Your Facts. It is Show (Me) Time

As that hypothetical developer in the introduction should have realized, being ready to request assistance can make the difference between receiving a solution or another question.

A senior developer may be able to bridge the gap between what is provided and what is missing, but that is a wasteful process where precious time is spent on gathering facts that do not require any domain expertise. Just like we shouldn’t use a torque wrench as a breaker bar or a scalpel to open a plastic bag, we shouldn’t use an expert’s time to gather basic facts about the problem.

“OK. How much information about the problem is information enough?”

This is a question of context.

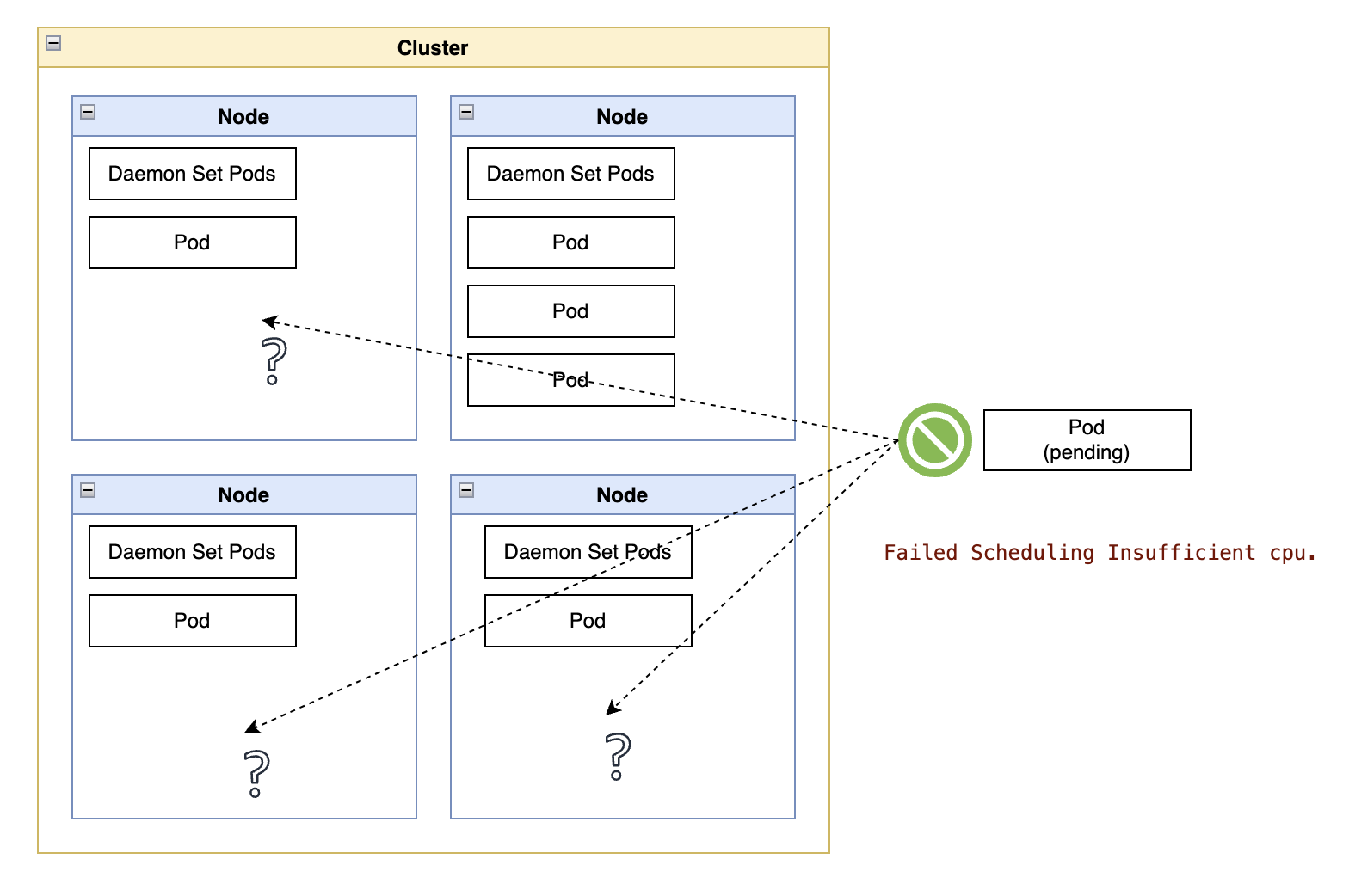

When you pose a problem to a colleague in the same project, you probably share a lot of contextual information about the project and any new issue - “It is that same problem we saw last week.” Conversely, a stranger maintaining an open-source project will need much more context about a problem you may face with their project. That is why reporting an issue with something like Kubernetes.io requires filling out a relatively thorough form template with several fields.

Following is a checklist I learned from a Critical Thinking coach many years ago, a couple of years into my first assignment as a team lead. I thought I was good at quantifying and qualifying problems until I met this coach, a retired manager in his mid-60s. He made a living by solving problems ranging from homeowner association disputes to CEO succession plans.

The “What?”

- What is the expected behavior of the product?

- What is the observed behavior in the product?

The “Where?”

- Does the reported problem happen to all units of the product?

- Does the reported problem affect the entire product or just portions of it? If so, describe the parts of the product.

- Does the reported problem happen in all locations where the product is used?

- Does the reported problem occur in combination with other issues?

The “When?”

- When did the problem start? If you don’t know, make it clear you don’t know and state when you first observed it.

- What is the frequency? Continuous, cyclic, or random?

- Is the problem specific to the phase in the product life cycle?

- Is the symptom stable or worsening?

Returning to the initial example in this article, when that anxious developer asked, _“My nginx server isn’t working. What could it be?”, can you spot everything that is wrong with it? In other words, could you expand the description to a point where an expert without familiarity with your system would not have to ask clarifying questions?

Going through the checklist, here are a few examples of questions I would be asking about the problem:

-

“What is the expected behavior of the product?” - Obviously, we want the nginx server to be working, which entails … what? An nginx server can serve diverse purposes, such as reverse proxying, load balancing, and caching. There is room for more precision here, but let’s enter a state of “suspended curiosity” and assume the developer means every possible function available on a typical nginx configuration.

-

“What is the observed behavior in the product?” - “Not working” is not a behavior. Is the server not starting? Is the server crashing after starting? Is the server rejecting connections? Is the server routing connections to the wrong handler? Is the server hanging while processing requests?

-

“Does the reported problem happen to all units of the product?” - Are there other nginx servers with a similar configuration working? For example, is this problem only happening on a single instance in a pool of nginx servers where all other nginx servers are working without issue?

-

“Does the reported problem affect the entire product or just portions of it? If so, describe the parts of the product.” This question goes back to the entire range of functions available on an nginx server. Is there any function that is working? For example, requests to a specific URL may return the expected results, but requests to other URLs hang indefinitely.

-

“Does the reported problem happen in all locations where the product is used?” If this nginx server template is deployed to multiple Cloud regions, is the problem localized to one or more regions but not all?

-

“When did the problem start?” Was it on a specific day where you have evidence of the functioning working on the day before? Was it immediately after a configuration change was applied to the environment? Note that this question may be the most difficult to answer because you may not have good observability practices placing the exact moment where the problem starts. In that case, report the first time you or someone noticed the problem.

-

“What is the frequency?” Are all requests failing, or are some of them going through? If some of them are going through, is there any pattern, such as failures happening continuously for a couple of hours and then working without issue for a few days?

-

“Is the problem specific to the phase in the product life cycle?” Does the problem only happen after the server was started for the first time after rebooting their hosting VM? Is the problem only happening after the server has been up for a week?

-

“Is the symptom stable or worsening?” If the problem happens randomly, is the average rate of request failures going up? If the issue only occurs after the server has been up for several days, is that number of days coming down?

Bonus Steps: The Team Side

The previous steps covered the individual responsibility aspect of tackling situations where we feel like we could use a hand.

Flip sides on the help-seeking contract, and there are also measures that the leadership team can put in place, from managers to senior individual contributors:

- Incorporate some version of the problem identification steps in the previous sections into regular onboarding and training sessions, setting the tone and the bar for all team members.

- Favor open-source libraries and components over home-grown bespoke systems. If you want individual team members to lean into crowd-source assistanced, you need to widen that coverage by using the same technologies and speaking the same language as the crowd.

- Promote and incentivize a culture of team collaboration. Push people toward communication in online forums and problem-tracking systems instead of private messages.

- Organize regular public post-mortem events where software developers and operations people review interesting bugs and outages. An engaging puzzle is at the heart of every bug and outage - just look at these.

A culture of tackling problem identification and dissection head-on is a culture of agency, resiliency, and self-sufficiency. Mutual assistance is still part of the social contract, but it is evenly distributed across offline and online interactions so that people can keep moving - staying engaged and motivated - even if they could use an extra hand.

Conclusion

The simple steps in this article can help professionals across all experience levels raise their individual problem-solving and problem-reporting skills. With some practice, people struggling with seemingly trivial issues will get stuck less frequently, keeping their motivation and momentum through tasks that felt impossible.

On the other side of the social contract, senior engineers working on a team that consistently follows those steps spend less time addressing basic questions and less energy trying to fill the gaps in questions and requests. With more disposable time comes a renewed focus on meaningful interactions and real progress.

For organizations, the newfound self-sufficiency and precision become gains in productivity, quality, and morale.

The best part is that anyone can practice these steps in a matter of days and experience the benefits immediately in their next few assignments.

Whether you are looking for help too often or you want to help others in more meaningful ways, consider the problem solved.