The Map to Where You Are Needed in Tech

Understand Change. Predict The Future.

|

|---|

| AI-Generated image by DALL·E |

The inspiration for this story started with another one, by David Caudill, titled Maybe Getting Rid of Your QA Team was Bad, Actually.

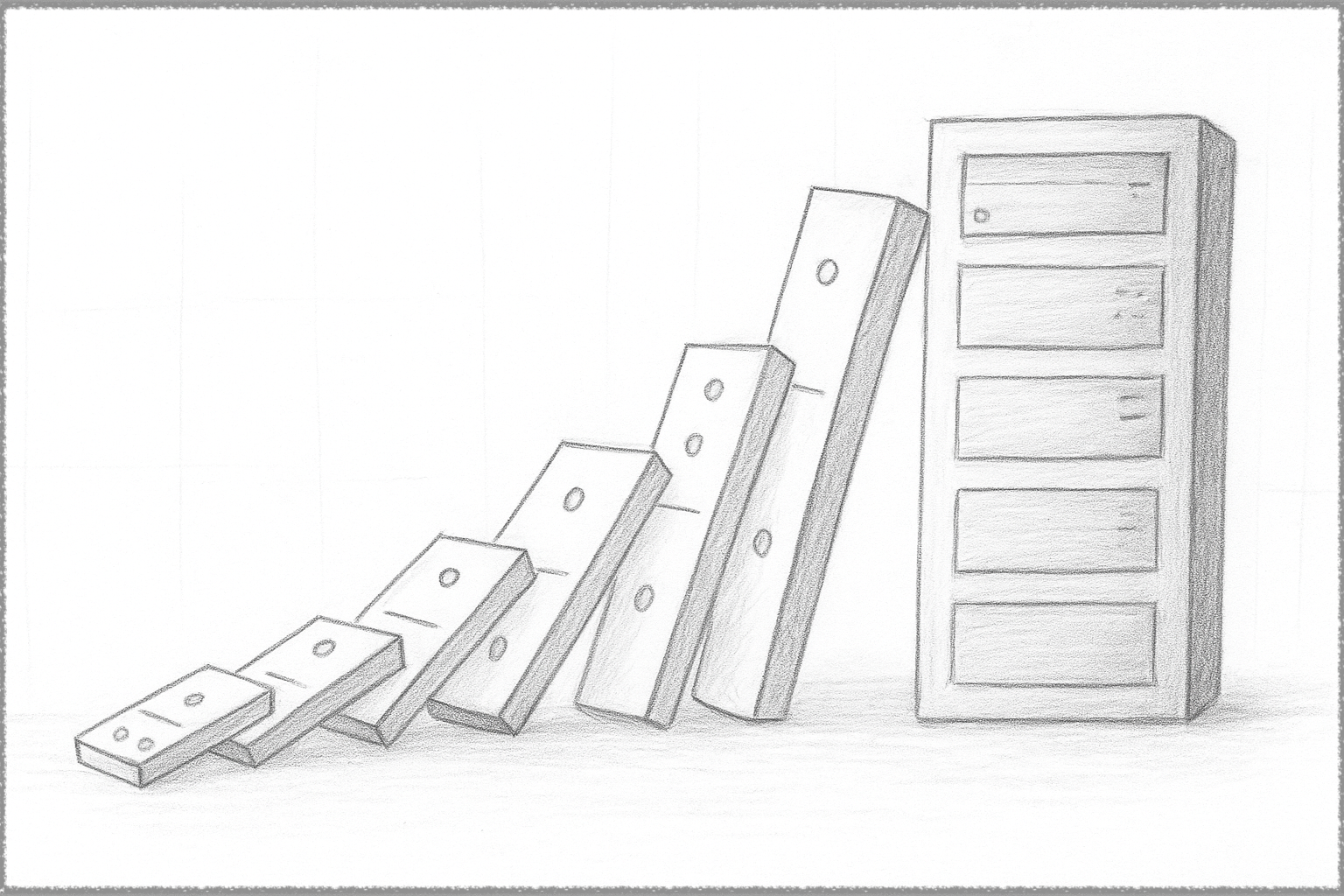

In that story, David takes the reader through a worrisome progression where organizations lose sight of quality over time and, in the process, progressively devalue the importance of QA engineering roles.

QA or not, there is a common theme of people observing fundamental changes in priority and starting wondering if their organization still has a place for them.

To use a traveling metaphor, unexpected changes in direction and surfaces can be disorienting and even hazardous.

The Map of Change

Tricky roads require maps, and when you need maps for anything that is not an actual road, look no further than Simon Wardley’s maps.

If you have never heard of “Wardley maps,” it is the best-kept secret this side of a business management school and a reliable way of understanding the landscape of any topic, whether you are looking at an emerging market or trying to figure out where the next career opportunities are heading.

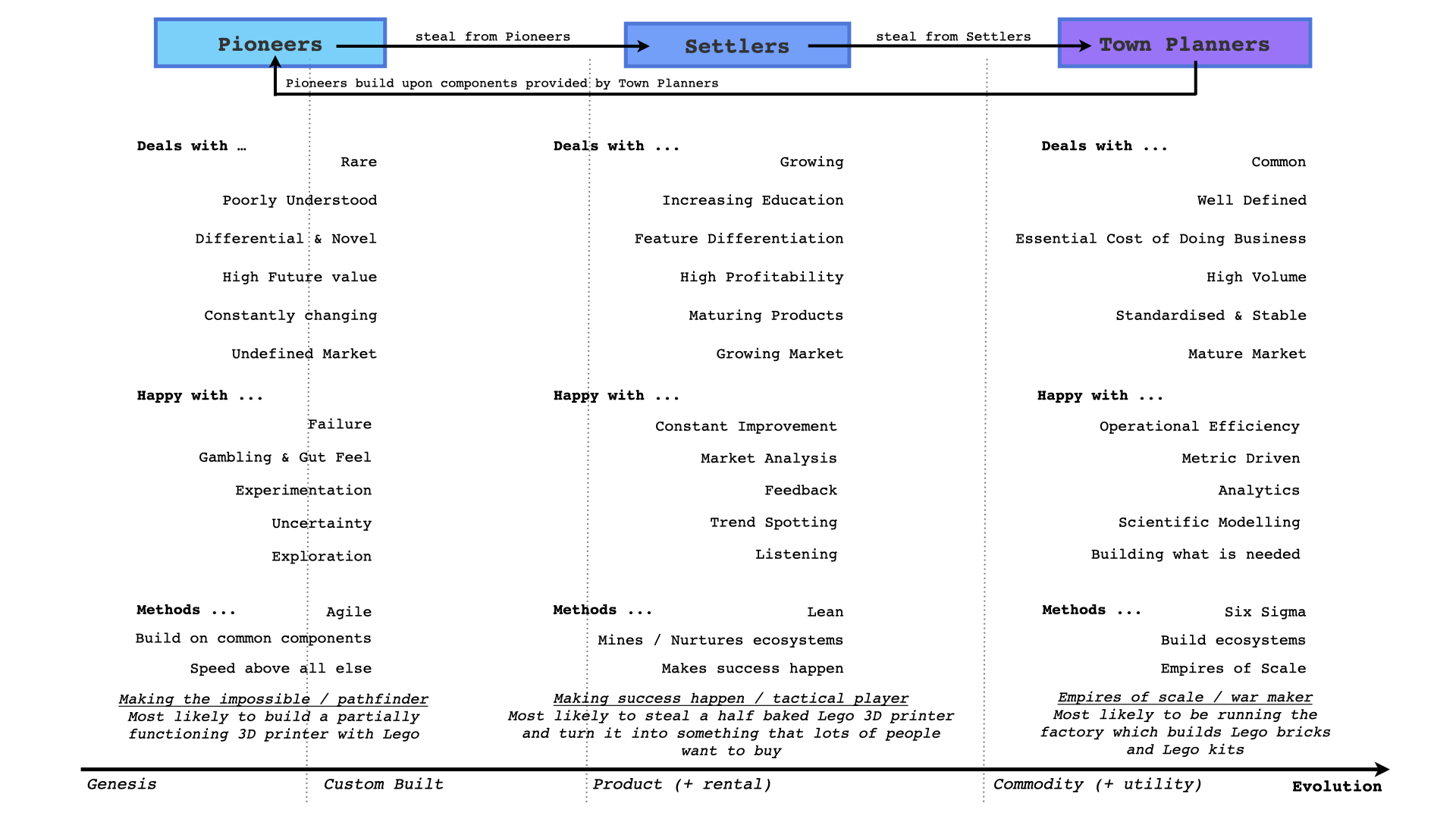

In one particular map, loosely titled “Pioneers, Settlers and Town Planners”, Simon describes the flow of evolution and change within organizations.

Understand that model, and you will start recognizing orderly flows where you would typically see random events and decisions.

In that model, there are three stereotypes for how organizations, small teams, and individuals fit into the change flows:

- Pioneers deal with rare opportunities in ill-defined areas, with a high risk of failure and high future value in case of success.

- Settlers deal with growing markets, high profitability, and the need for adaptability to changing conditions in those markets.

- Town Planners deal with well-defined, already established areas. They focus on delivering high volume with discipline in process and cost controls.

For the remainder of this story, I will refer to Simon’s model after the initials of each stereotype: PST.

Ugly Ducklings and Egos

Like in the story of the ugly duckling, even the most competent individual will underperform in the wrong setting.

While every large organization has a set distribution of resources across the three pillars of the PST model, individuals can only be excellent in one pillar at a time.

For example, someone tasked with writing a prototype for a new market should not be asked to observe rigid standards of DevSecOps discipline.

Conversely, a QA engineer who is excellent at creating automated processes and structured guidance for a growing product - aligned with a “settler” role - may struggle to contribute value in a research organization with shorter project spans and higher failure rates.

A few readers will try to make the case that an individual can be simultaneously excellent in two adjacent pillars, such as “Settler” and “Town Planner.” Before making that argument, however, they should make sure their example was not someone always moving Kanban cards on a board while people worked on their email backlog - been there.

Unlike in the Danish fairy tale, a poor fit between individual tendencies and PST pillars runs deeper than the length of feathers or the shape of beaks.

How deep?

Take it from Jörg Heitkötter, who while remarking on an article on Simon Wardley maps, pushed right across the lines of Nature over Nurture, and contrasted personal interests against the dimensions of the PST model:

Ego vs. Company interest

It occurs to me that one interesting “feature” of pioneers, settlers, and town planners has not been stated or investigated in the model yet:

Pioneers tend to have an ego they put over the company; at the other end of the spectrum, Town planners tend to put the company over their ego and do what’s best for the company, while Settlers tend to be in equilibrium with regard to ego vs. company interests.

This might be helpful for HR people or managers to identify the right members for their teams, sorting out the fake Pioneers/Settlers/Town planners from the real ones.

This topic of personal and corporate interest opened my eyes to better ways of identifying and relating to a handful of team dynamics I would consider troubling otherwise.

What opened my eyes was the realization that shifting from one pillar to another may entail a change in personal values and in how individuals relate to their institutions. When people say they are not sure they can adapt to a different PST pillar, they may be balking at changing their entire outlook in life.

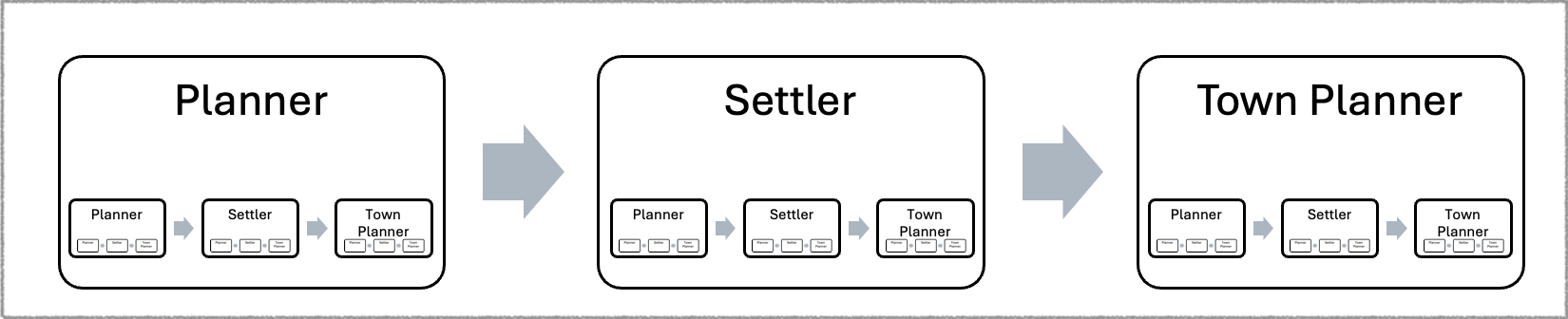

The Fractal of Change

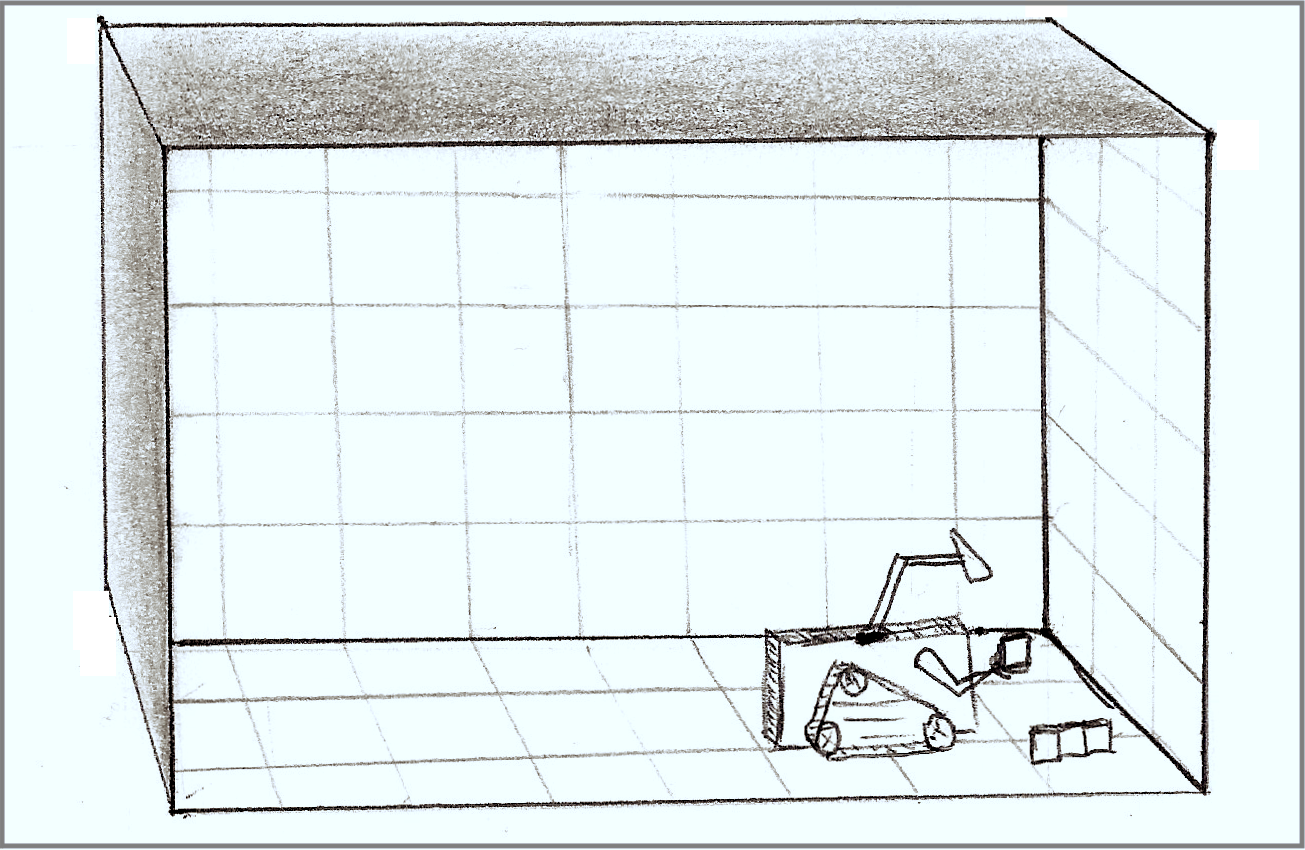

The pattern of PST roles of change in an organization repeats itself in smaller parts, down to the individuals in that organization, forming a fractal dimension. In other words, a smaller part of an organization primarily focused on one pillar, such as research, still needs to apportion its resources in a PST framework.

Naturally, each pillar still needs to focus and specialize in its primary function, but within each pillar, smaller change flows require attention, too.

Balancing that allocation across all levels is the recipe for sustained success.

Neglect the exploration of the new and innovation stalls. Neglect the elaboration of a promising activity and growth stalls. Ignore the day-to-day work management, and long-term success becomes impossible.

That goes for individuals, too.

|

|---|

| Fractal of change: On a smaller scale, each role presents opportunities for another continuum of change containing the same roles. |

Balance it right, and the pioneering side of an enterprise may reveal new paths that eventually transform the entire business.

Look no further than my favorite example of sustained business transformation: Nintendo.

Nintendo has a tumultuous history spanning over 100 years, starting as a playing card company in the late 19th century.

Nintendo was successful for decades, then struggled, then partnered with Disney in the 1950s, found success again, and went back to struggling in the 1960s.

At some point during that struggle, Nintendo tried everything in sight to get out of the slump, from manufacturing food to vacuum cleaners and toys.

And how did Nintendo transition out of stagnation in the 1960s?

Through the creativity of a maintenance engineer turned product designer:

In 1966, Yamauchi [Nintendo’s President at the time], upon visiting one of the company’s […] factories, noticed an extending arm-shaped toy, which had been made by one of its maintenance engineers, Gunpei Yokoi, for fun. Yamauchi ordered Yokoi to develop it as a proper product for the Christmas rush. Released as the Ultra Hand, it became one of Nintendo’s earliest toy blockbusters, selling over hundreds of thousands units. […] Yokoi was soon moved from maintenance duty to product development.

Due to his electrical engineering background, it soon became apparent that Yokoi was quite adept at developing electronic toys. These devices had a much higher novelty value than traditional toys, allowing Nintendo to charge a higher price margin for each product. Yokoi went on to develop many other toys, including the Ten Billion Barrel puzzle, a baseball throwing machine called the Ultra Machine, and a Love Tester.

Fun fact: Nintendo still makes playing cards

When Change Requires Theft

Earlier in this story, you may have noticed the “stealing” references between roles in the PST model, with settlers stealing from pioneers, town planners stealing from settlers, and pioneers borrowing components from town planning resources.

It may not sound good, but it makes perfect sense.

As pioneers find something with growth potential, it is time for settlers to make that growth happen. That transition is never smooth because settlers may appropriate the tools and techniques and even deprive pioneers of the credit. Look no further than the contentious debate about Elon Musk being a pioneer or a settler in the founding of Tesla Motors.

As a business reaches a certain status and becomes a commercial success, it is natural to “industrialize” the money-making sectors of that business, multiplying the profits per unit across more units. The search for differentiation and adaptation, a vital aspect of the settler routine, is the enemy of efficiencies and maximum gains.

And when everything is organized for maximum efficiency to the detriment of all else, it is time for the organization to carve out resources to form an expeditionary force of pioneers.

The circle of change is complete, and once again, the same goes for individuals:

- “That idea was mine” precedes the hard truth that the pioneer behind it was content to have the idea and not explore it.

- “They stopped investing in our project” precedes the reality that the project peaked a couple of years ago.

- “Some people get to have fun exploring new things” negates the reality that new ideas and opportunities keep the organization adaptable to changes in the environment.

Once again, the same goes for individuals, who may overstay in a productive role where their skills are a perfect fit for their project needs. In that stagnant arrangement, everything they know is useful to the project, their importance grows, and their careers grow steadily.

As projects and products inevitably reach a plateau and start to decline, successful software developers may suddenly find themselves at the top of the wrong hill.

They miss their exit turn.

Master of Journeys, not Destinations

To bring the theory full circle toward practice, let’s use the dispirited trek of our QA colleagues in the story opening. Organizations focusing heavily on town planning activities need quality control more than quality assurance.

Conversely, portions of the organization pioneering new technologies may not have much output to worry about quality controls or assurances. Awareness of the territory tells QA engineers to seek roles in growth areas where quality matters and the nature of what is measured is constantly changing.

Yes, I am saying QA engineers, at their core, are settlers.

But can a settler-at-heart thrive in town planning? Yes, it is a fractal of change, remember?

As the business looks to streamline processes, often through automation, there is still room for fewer individuals to develop new techniques to optimize the processes.

A Case Study in Adaptation

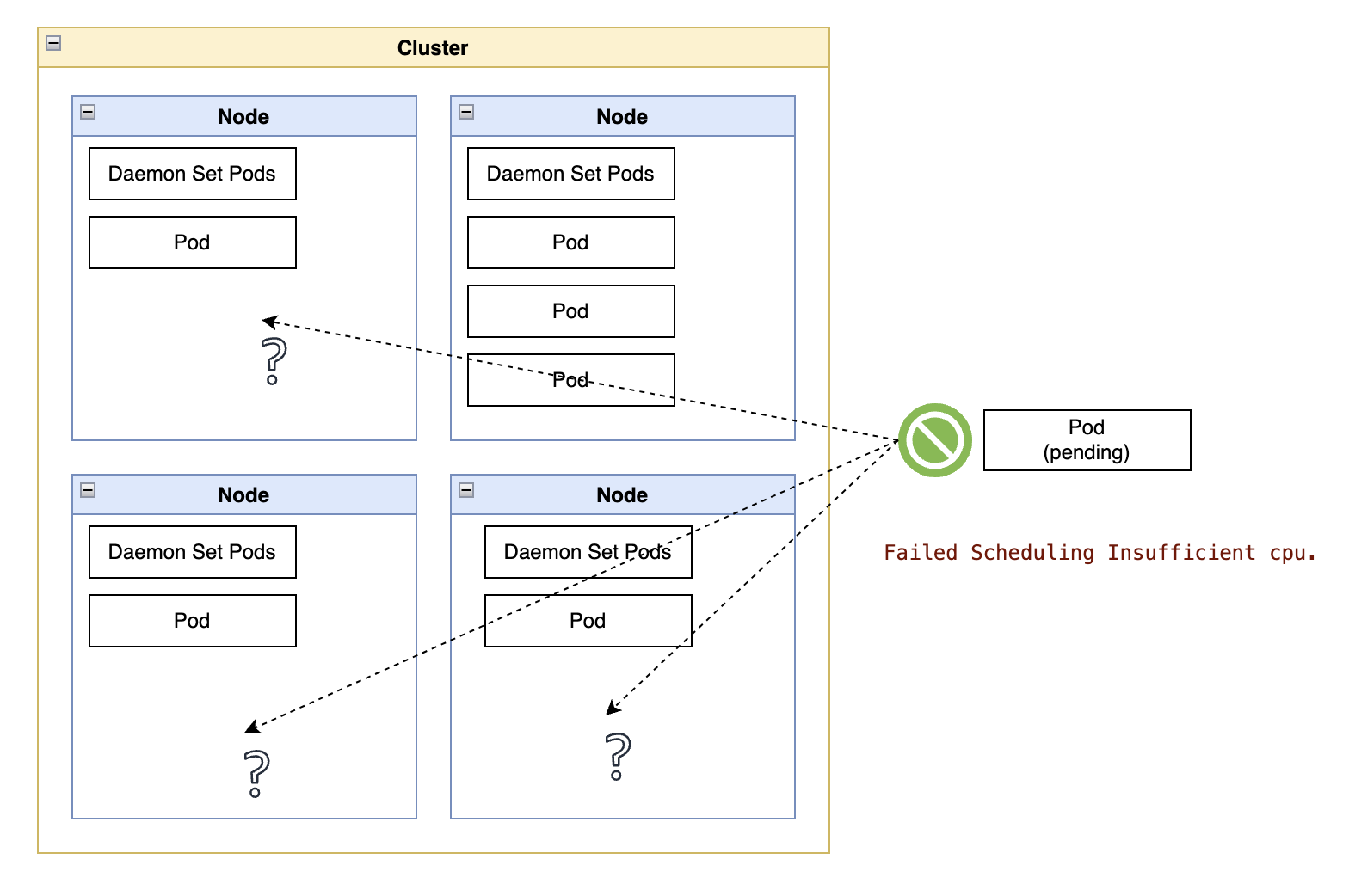

As a concrete example, let’s say you work in the QA activities for a mature product line. You then automate a process that simulates chaos in the environment running the product code. The simulation would include things such as turning off network firewall rules, restarting VMs, killing processes, and such.

Since these simulators already exist, building a new process around them is a “settler” principle (reusing existing technology developed by pioneers). And the new process can be applied to an organization in “town planning” mode, introducing a low-cost approach that can be embedded into other quality control pipelines.

Take that idea a step further; you can pair up with an SRE team to embed that new process into the early stages of a SaaS pipeline. Now, we have the potential to notify software developers about the high-availability characteristics of their code changes in the context of their pull requests.

Take that potential even further, and such technology can create chaos in a production environment and gauge its resiliency in the face of actual outages.

Is that pioneering?

Not really; Netflix did it some nine years ago. Remember, settlers steal from pioneers - and I am not talking about stealing credit, just the output.

There is Always a Path

If you are not a software developer but feel like software developers get all the credit, the way forward is to inject more coding into your work.

For example, if you are a technical writer and your product has an API, create a better way of validating code samples in documentation examples. If the product only has a graphical user interface, find a way to use LLMs to generate documentation pages while a bot monitors users iterating with the product interface. There is (almost) always a way.

And if you are an SRE, we are living through a golden age of opportunity for AI-assisted operations, with LLMs increasingly showing potential in helping people formulate commands during critsits or perform basic troubleshooting assessments.

Keep Moving, Keep Building

On a smaller scale, because the map of change flows is a fractal of smaller PST models, even being in the “wrong” PST pillar for your working style does not mean a life sentence of devaluation and disgruntlement:

- Even the most pioneering teams need some order.

- Even the fastest-growing businesses need standardization and stability to avoid chaos.

- Even the most profitable mature business can use innovation in smaller uncharted processes.

While these smaller actions can make you more valuable to your organization - and happier, too - the moral of the story is that when the only constant is change, becoming a specialist in navigating change is a core competence to succeed in our profession.

And now you have a map, too.

As long as you are willing to keep moving, your present situation is just a stop on the way to where the organization needs you.

If commerce downtown is too crowded or life as a shopkeeper is not for you, there is always money to be made transporting goods across town limits or erecting new buildings.

If something doesn’t exist, create it.

If it exists and is valuable, build upon it.

If something works, keep doing it, but keep looking for the next thing.