Are You About to Leave the Cloud?

Make your travel preparation list for the long journey ahead.

|

|---|

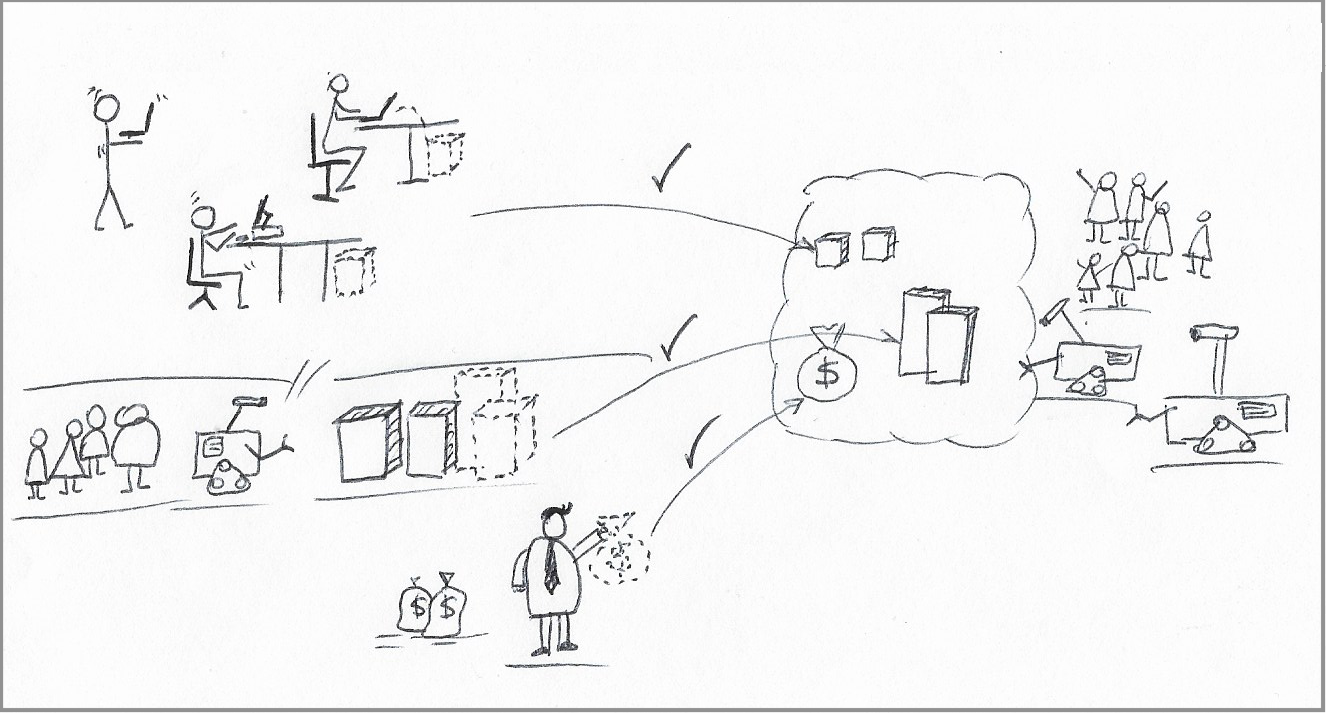

| While moving from on-premises to the Cloud and back, the core stakeholders are developers, operators, and finance people (including product managers. |

Cloud spending is always an exciting topic, and I mean exciting in the wrong way.

Money is a sensitive subject, and people get understandably nervous when they feel they may lose their grip on the budget. But how do you keep a handle on the budget when the things you are paying for don’t look like anything in the past?

Finance people get anxious about a seemingly uncapped monthly expense, and operations people get frustrated with an ever-growing share of their budget going towards leasing Cloud capacity.

Wedged between both camps, we find developers increasingly relying on the Cloud for central, and sometimes irreplaceable, portions of product design and runtime. Keep a close eye on this group of stakeholders as you read along because their actions ultimately upended the Cloud adoption trajectory.

This story is about what we need to understand heading into the next stage of Cloud adoption. Before getting to that next stage, and acknowledging that this new phase may be the first contact with the Cloud for many people, let’s get started with a quick recap of how we got to the Cloud. This recap also sets the context for when you hear the siren songs of the “leaving the cloud” movement.

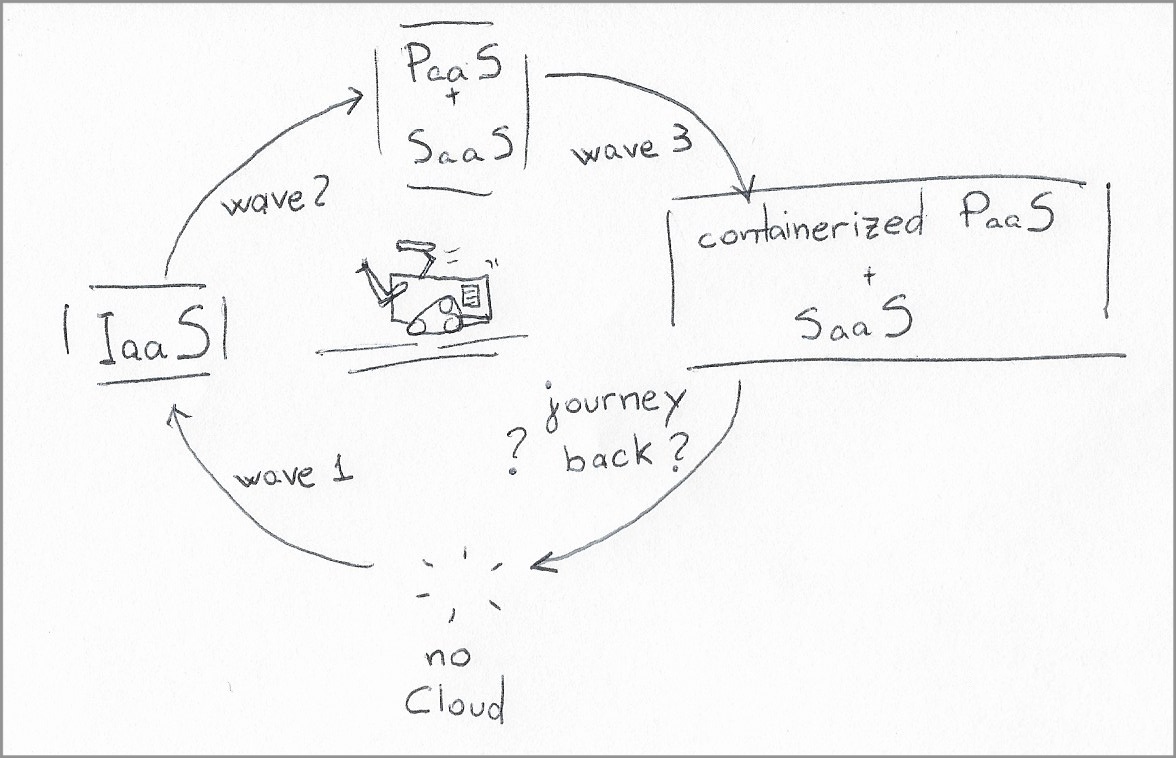

Wave #1: Resource consolidation

This first wave of migration to the Cloud was, at the same time, ground-breaking and straightforward. It was the age of “Infrastructure As A Service.”

For the benefit of the kids in the back, up to this moment, every company ran their data center, and software developers ran a shady underground of virtual infrastructure under their desks. “The overnight cleaning staff tripped on a cable” was a plausible explanation for a build failure.

Servers progressively migrated from under developers’ desks toward in-house data centers. Once consolidated and depreciated, the server capacity slowly climbed regulatory and technological barriers toward remote data centers on “the Cloud.”

Developers did not care about the migration as long as they could still have terminals to the computing capacity and as long as those computers ran their operating system of choice. And if we are honest, those personal servers could be quite the distraction after a botched upgrade, often costing entire mornings or even days to be reloaded.

Finance people managed the transition in a comfortable environment. They could deliberately compare the status-quo costs of hosting capacity on-premises with Cloud provider estimates, only then approving beneficial trade-offs. Meanwhile, Cloud providers were cautious to keep prices under the magical threshold where that math kept making sense.

Operations people saw servers and cables gradually disappear from their data centers. The manual labor, like carting racks and running cables, was mostly gone, but managing the resulting infrastructure was just as complex as before. When the business needed new computers or network paths, operations people used a cloud management console to replicate the requests. Still, they needed a firm grasp on configuring servers, allocating storage, and forging secure communication paths among parties. Being able to refocus their effort on their core mission and not seeing an immediate threat to their job security, they, too, welcomed the transition.

|

|---|

| In the first wave of Cloud migrations, physical servers move to a Cloud provider, and everyone welcomes the change. |

Wave #2: Outsourcing the middle layer

Middleware, also known as “glue software,” sits between layers implementing domain-specific logic and the infrastructure, hence the “middle” portion of the moniker.

Database managers, transaction managers, and messaging servers are classic examples of middleware. The function was (and remains) generic, but the implementations are staggeringly complex, with price tags to match.

Beyond the license costs were the attendant costs of the requisite army of people responsible for deployment, operations, and, last but not least, the seven-headed beast of data management.

With middleware playing a central role in moving and storing business data, there was little room for improvisation before the legal department started sending embarrassing letters to customers, so there was equally little room for cutting corners in the operations budget.

Only a few large companies (or projects within large companies) had deployments large enough to justify a permanent pocket of engineers specialized in a given middleware technology.

Besides those large companies running their own applications, only a small set of companies could match and exceed the prerequisite scale of operations: Cloud providers.

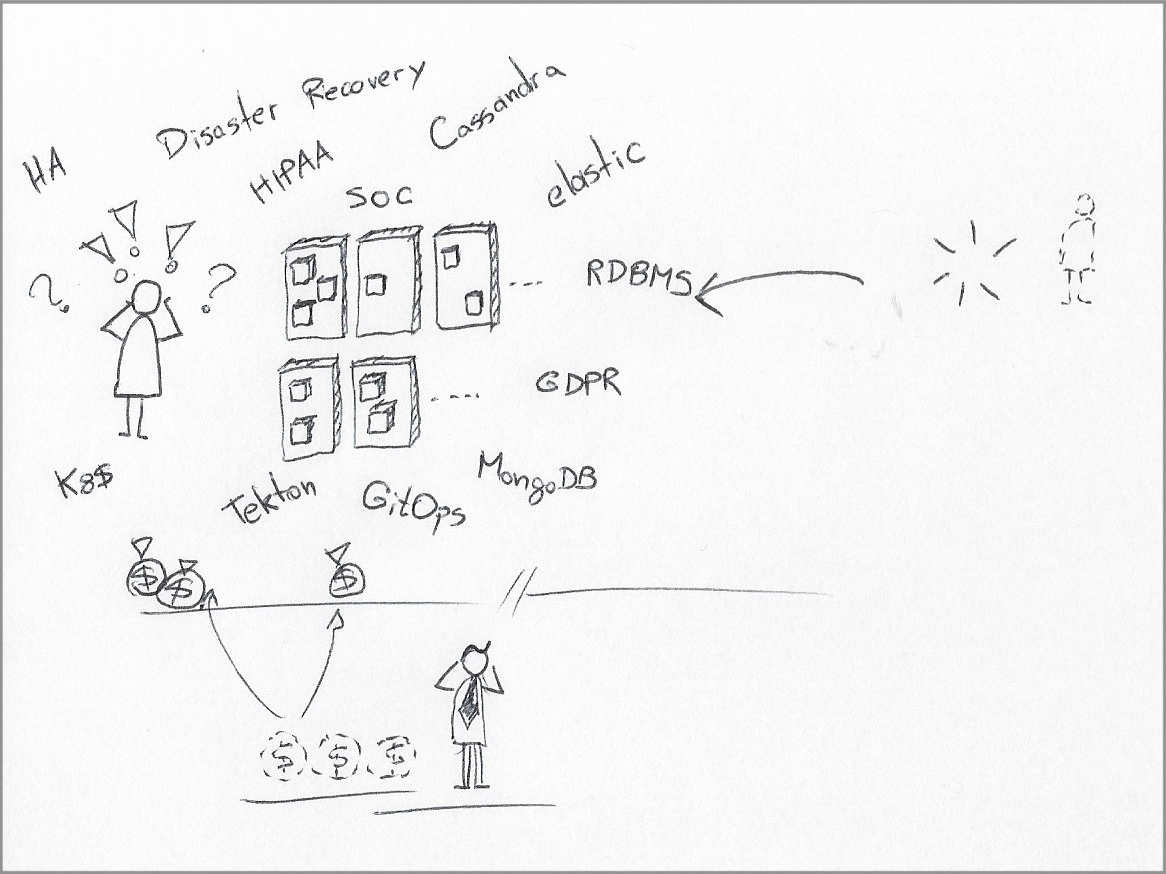

Once again, those providers climbed regulatory hurdles (HIPAA, GDPR, SOC) and technology limits to make managed middleware services a reality.

Developers still retained responsibility for data architecture, modeling, and processing. With business logic already running remotely, it did not matter whose servers were running the middleware for the applications. Developers were happy as long as performance was comparable and system interfaces - largely operating system interfaces - remained stable.

Operations may have felt this wave was a little different, as it took away some of their responsibilities. High availability, resiliency, storage management, data security, and disaster recovery were gone. These were (and still are) complicated activities requiring specialized personnel and were no longer needed on-premises in similar volumes.

To illustrate the point to people unfamiliar with operating middleware, it was not uncommon to have engineers spending the equivalent of multiple person-years writing bespoke automated procedures to deploy and manage a high-availability pair of database servers.

Finance people may also have struggled more with this stage because it meant shifting funds from operations personnel to services. While managers may not have cared where servers were running, losing staff was a much more sensitive discussion.

|

|---|

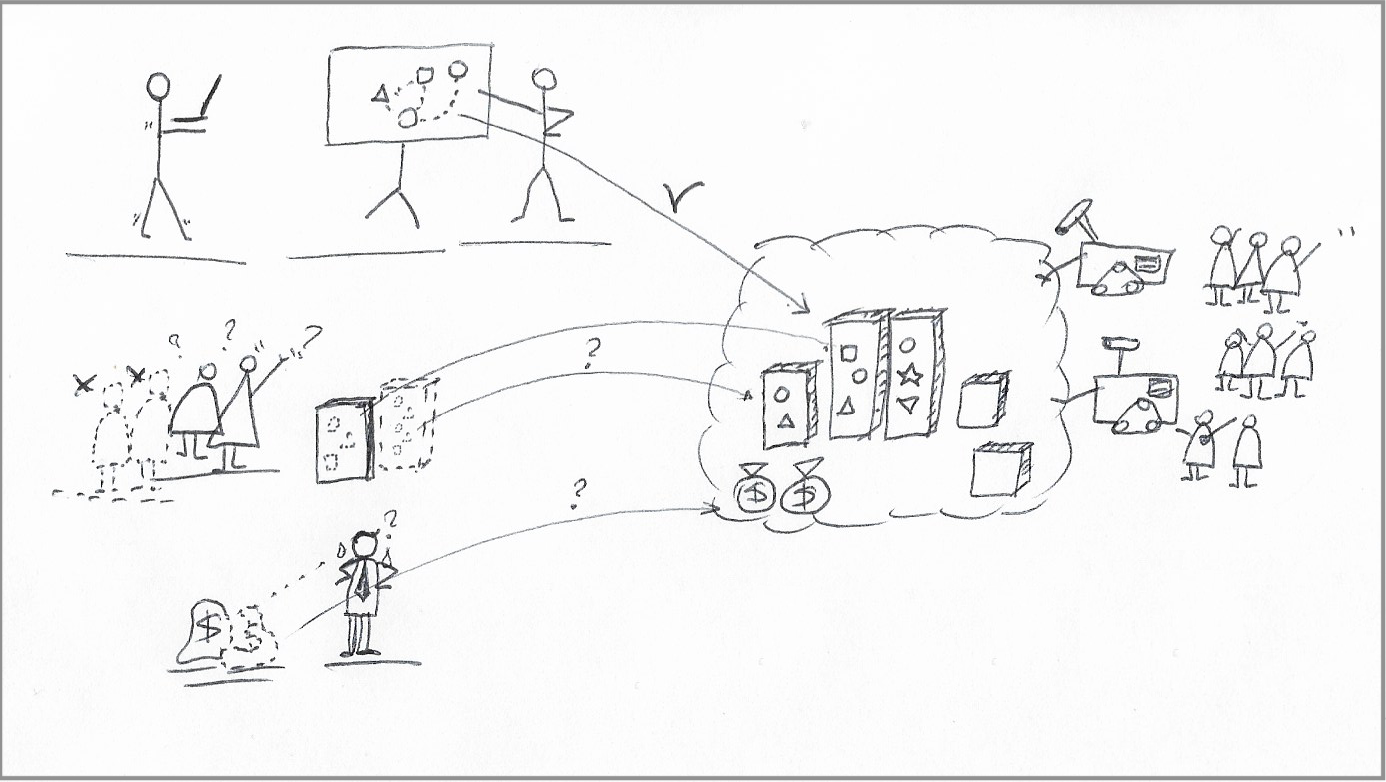

| Middleware services move to the Cloud during the next migration wave. Operations teams lose a few people, and more of the budget shift toward Cloud services. |

Wave #3: The age of containerization

With infrastructure and services firmly in the Cloud, the next abstraction was packaging and running code in the infrastructure. Heroku and, for a while, Pivotal established the concept of “push-and-run” for applications, leveraging a smattering of managed service offerings for popular middleware such as PostgreSQL, MongoDB, and Redis.

The real winner, however, emerged around 2016, during the container orchestration wars between Docker and Kubernetes: containers.

As it turned out, virtual machines were a wasteful and unwieldy packaging format for shipping applications. Containers, on the other hand, solved the waste and packaging problems while still looking close enough to an operating system for developers who cared about it.

A companion development was the proliferation of container image registry services and an emergent industry of continuous integration (CI) services. These CI services were also built atop containers, with container-based orchestration (Tekton CD) and container-based image creation (Buildah, Buildkit, Podman, etc.)

At this stage, containers became the de-facto unit of development, build, packaging, and execution. If someone asked how the Cloud worked, you could reasonably describe it as a stack of containers running atop containers, all the way down.

|

|---|

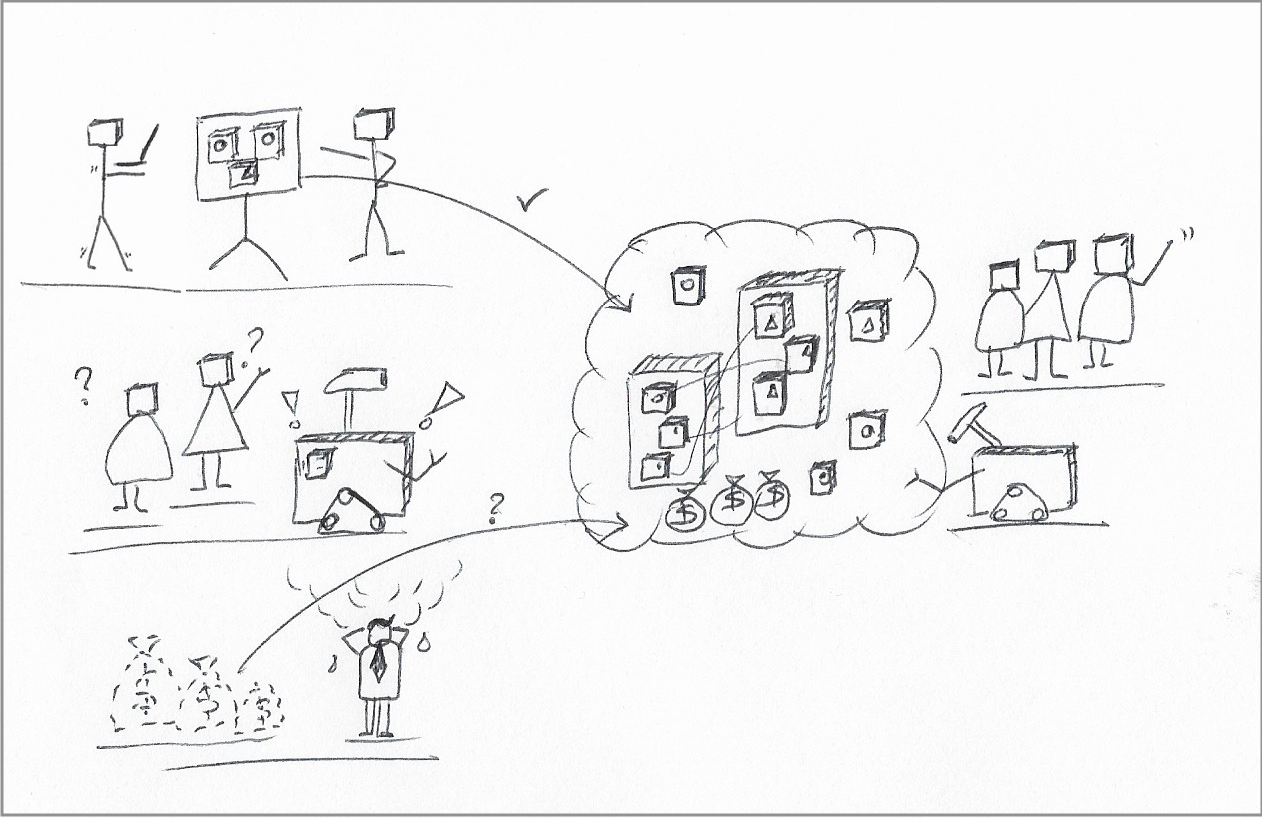

| Containers, containers, containers. Applications, middleware, continuous integration pipelines, continuous deployment, runtime engines, packaging. Everything is a container. |

From the sidelines, we also saw some progress in the FaaS camp, primarily as an event handler for managed services. While FaaS could also handle other asynchronous events, its development and packaging model was conspicuously different from the now dominant container model. With a proliferation of container services that could process many of those same events, FaaS adoption remained a relatively niche practice.

When we look at this stage from the perspective of our stakeholders, we still see developers more or less unaffected by yet another significant shift. For developers, containers still offered a runtime and filesystem interface akin to an operating system, so application code ran virtually unchanged.

Containers also addressed an evolving demand for lift-and-shift scenarios for server-side components unavailable as managed services. Lastly, a standardized packaging and runtime format allowed the same software to run virtually unmodified on local and remote machines. A seamless transition from local to remote environments meant a closer alignment between local development loops and production environments. It is not that developers were indifferent to this wave; they cheered on it.

For operations people, this wave felt very different. The familiar operating system interfaces for application runtimes were gone, and they needed to retool their practices considerably. Every runbook, troubleshooting, log management, monitoring, and deployment procedure had to be revisited, rewired, or rewritten. Every meaningful application management task now happened in the container layer.

New entrants redefined the vendor scene for infrastructure and platform management, waltzing through a landscape free of incumbent products and unburdened with the upkeep costs of legacy offerings. One key aspect of this evolution in IT tools was the diversity of service offerings and reasonably sophisticated open-source projects that could handle the operational loads of large systems. Operations teams could create cohesive management platforms that would have been unthinkable in the past.

For finance people, that was the first wave where things felt significantly different. The budget line items looked different, and there were fewer requests to replace the aging hardware that had survived the first two waves of Cloud migration. On the other hand, operations and development required subscriptions to new SaaS offerings and were hungry for service instances in their Cloud providers.

Attempts at curbing budgets with draconian controls backfired, with internal platform engineering teams being crushed by exponential increases in demand from operations and development teams.

Suddenly OpEx was the new CaPex.

A New Home With a New Architecture

In another stop before we look back to on-premises deployments, let’s pause to understand where the industry sat after the preceding waves of Cloud migration.

I picked a few salient categories and generalized what one could consider the state of the art if starting a new architecture from a blank slate today:

Runtime: Native apps running on bare-metal servers gave way to virtualized hardware and, subsequently, to containers running atop Kubernetes or managed container services. Functions round out the picture for use cases where applications need to process events from a managed service.

Packaging: Container images become the de-facto distribution format for applications and middleware, making container registries and build services an integral part of a software development process. Package managers such as npm and maven central are still very much needed inside container builds.

Continuous integration (CI): The standardization around container images spreads across all build pipeline vendors. Developers expect CI tools to have native support for building container images, preferably from something as simple as the URL of a Git repository containing a Dockerfile.

Architecture: The economies of scale in the Cloud enables the business case for various middleware offerings that had not been possible before. Cloud providers boast service catalogs with hundreds of offerings. Many offerings are “cloud native” (only available through a Cloud provider.) As a result, new software architectures incorporate capabilities that did not exist ten years ago. Without a reason to consider an eventual shift to on-premises deployments, many architectures now include “long-tail” services that would be cost-prohibitive for individual companies without massive economies of scale.

Budget: A reduced infrastructure and service footprint on-premise means a conversion of CaPex into OpEx. The increasing dependency on Cloud-based services means developers and CI pipelines have a newfound hunger for Cloud resources. Continuous Delivery models increasingly rely on multi-stage pipelines (dev/test/stage/prod/others), further multiplying resource consumption. Now overseeing a considerably smaller physical infrastructure and service footprint, operations teams are gutted in size and breadth of skills.

|

|---|

| After successive waves of migration, from infrastructure to services, the journey back from the Cloud is an uncharted step forward rather than threading back through the old path. |

Check your (invoice) baggage before the trip

(I promise this is the last stop before looking at the on-premises journey.)

Anyone managing a large Cloud account knows (or should know) that different cost models are appropriate for different usage patterns.

As a quick recap, let’s look at the most common pricing models across major Cloud providers. Note that Cloud customers can combine different pricing models for different resources within the account.

-

Pay-as-you-go: Pay a variable monthly bill for actual usage in that billing cycle. This model is the costliest in terms of cost per time unit (typically hours or seconds) but also the most flexible.

-

Prepaid/subscriptions: Pay a fixed monthly (or yearly) bill for a service package. It does not matter when you consume the contracted services during the billing period. You must pay more if you need more services above the contracted package during that period.

-

Reserved instances: As the name suggests, you book resource capacity, typically over a relatively long period, such as 1 or 3 years. When you need more than what is reserved, you pay a higher hourly rate for the excess consumption.

-

Spot instances: You request computing capacity from a pool of spare capacity for a significantly discounted hourly rate. The caveat is that the Cloud provider may reclaim the compute instances on short notice (typically a couple of minutes.)

Before heading into the next section, I assume people wanting to leave the Cloud have already looked deep into their bills, usage history, and use cases to make simple cost-saving decisions such as:

-

Allocating reserved capacity for long-term requirements instead of using more expensive on-demand capacity.

-

Using a cost-per-invocation service (function or containers as a service) for low-volume operations instead of idling (and paying for) reserved capacity.

-

Work with the account manager to obtain volume-based discounts.

-

Use spot instances for workloads that can tolerate disruptions and don’t need stringent qualities of service - For Kubernetes shops, check out my posting on auto-scaling workloads using spot instances.

-

Hire a specialized Cloud cost-management consultancy. In many cases, their services may pay for themselves with savings within a couple of billing cycles.

After following these steps, you may still feel like your Cloud bill is too high and decide to plunge head-first into the next section. However, that migration will undoubtedly take a while. It never hurts to be spending less every month while your organization goes through that process.

“That is it! We are leaving the Cloud!”

When virtually every company in the world has a Cloud footprint, isolated opinions quickly form an undercurrent. And that undercurrent is that using Cloud resources has become too expensive.

More recently, Basecamp reignited (or maybe helped coalesce) the debate with this blog posting about leaving the Cloud. You can listen to the companion podcast episode adding more context about the impending departure.

However, both the posting and the podcast need more details about their current and future system architecture.

“Future system architecture, you say?”

Yes. Architecture and costs go hand-in-hand. I am not privy to the technical details behind Basecamp’s move. Still, they talk about cutting the costs of using services like AWS RDS (database) and ES (search,) for which they will need to find replacements.

|

|---|

| Development, operations, and product managers must travel and arrive together on their journey back to on-premises deployment. |

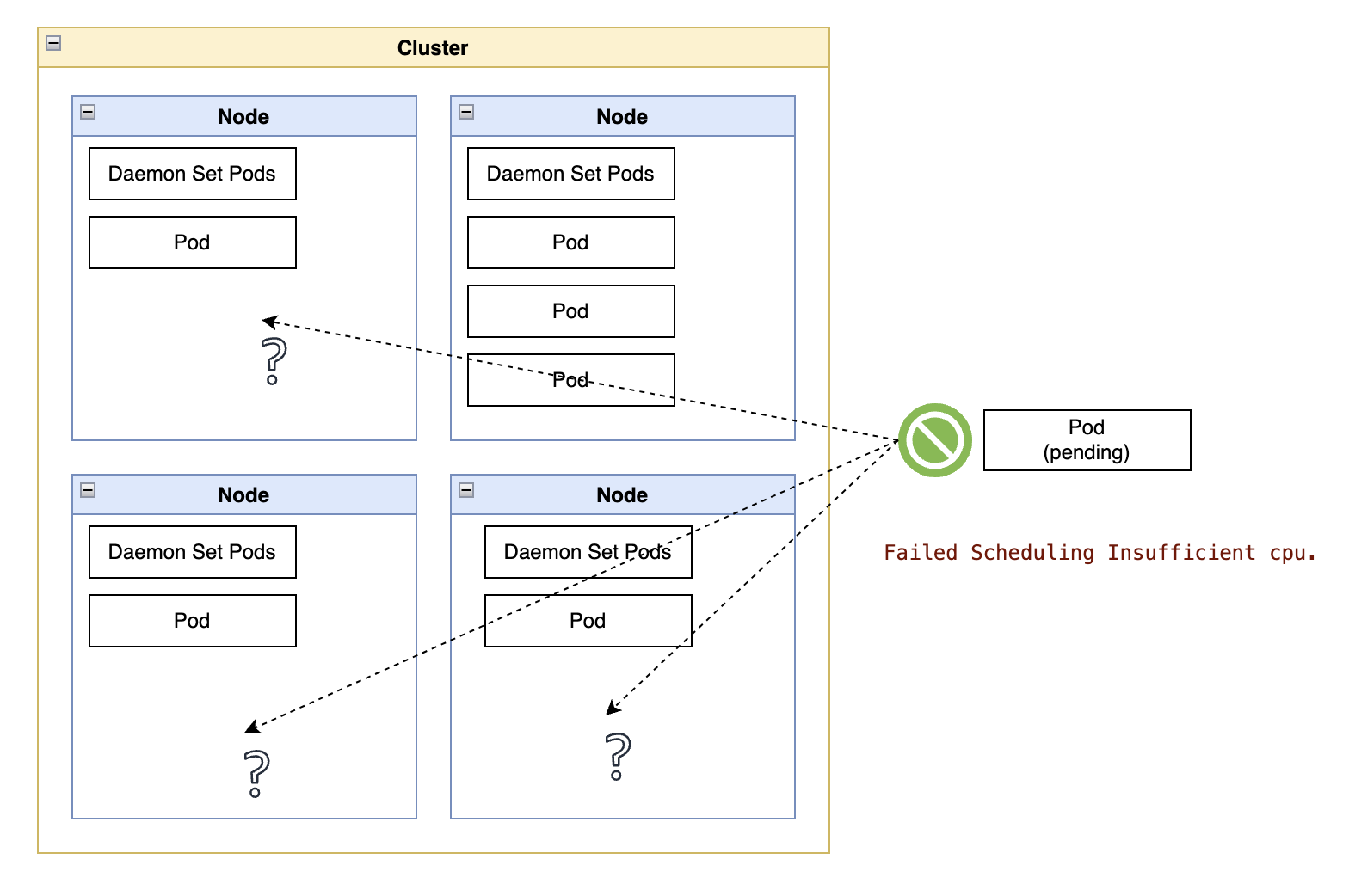

There is never a straight, unimpeded road from the Cloud to an on-premises deployment. Here is a list of pitfalls and concerns lining that road:

Network egress costs. Cloud providers will happily wave your data into their premises but, with few exceptions, will charge you for retrieving the data, typically by volume. In other words, you will need to watch out for hybrid topologies where one component on-premises continuously extracts large volumes of data from components still hosted on the Cloud. Some of those hybrid topologies may even be unintentional, with a re-hosted component suddenly requiring more synchronization checks with the components still hosted in the Cloud provider.

Operational skills. Before bringing any Cloud-based service in-house, consult your operations team about the availability of those skills within the group.

However boring for a system administrator, repetition and specialization are pillars of productivity. Repetition leads to automation, and specialization leads to deep expertise. Deep expertise is where senior engineers can be several times more productive than those inexperienced in that technology.

For many disciplines, like database administration, the skill gap goes beyond the performance differential. Below a certain threshold, the entire organization starts risking catastrophic cases of the Dunning-Kruger effect, where they feel confident about the discipline. Until the first outage, that is.

The fragmentation of operations personnel to cover fundamentally different technologies dilutes repetition and specialization while increasing overall stress with more frequent context-switching.

Insufficient runtime scale. Some Cloud-based services only make financial sense after surpassing a critical size threshold. The break-even point of some services may be dozens or hundreds of customers. It is rarely a handful, or worse, one.

In the best-case scenario, you may skip the R&D costs by deploying the same middleware underpinning the Cloud service (such as MongoDB or PostgreSQL.) Worst case, the service is a proprietary Cloud-only service such as speech-to-text.

Even in the best-case scenarios, running something like a small cluster of PostgreSQL instances, no matter how lightly loaded, still takes many fixed-cost infrastructure configuration steps. And after the initial configuration, there are also the “day 2” activities, such as automating upgrade cycles, backup procedures, governance, configuration management, and many others.

Insufficient operational scale: This topic combines the previous two. Operations teams scale better “horizontally” (larger footprints of the same technology) than “vertically” (smaller deployments of multiple technologies.)

I covered the aspects of repetition and specialization but left out on-call schedules. Typical baseline numbers for a 24x7 on-call rotation suggest a team of 6–8 people, with actual numbers depending on the average volume and nature of page outs.

That baseline assumes that people on the rotation are equally capable of handling an eventual outage. You will not find many people who can equally fix something deep in the operation system (such as a detached disk) and high up in the middleware stack (such as a messaging dead-letter queue getting full.)

A disconcertingly common mistake for operation leaders is ignoring the total number of alerts a system can generate when sizing the on-call rotation - I covered the stressors of being on call in this article - One of the primary sources of stress is the uncertainty about having the skills, tools, and support to handle the situation. A rapid explosion in the variety of services on-premises is a recipe for paging someone who cannot address the problem and collapsing the effectiveness of existing on-call schedules.

One common and somewhat valid counter-argument is that Cloud services still require operations teams, and re-hosting services on-premises should not increase workloads. While it is true that a managed service still requires operational procedures – What if Cloud instance X needs a configuration change? What if Cloud service Y goes down? – the variety and complexity of skills are technically less demanding than managing the service. When a database instance suddenly disappears from the Cloud, you need someone who can characterize the problem in a support ticket, not a specialist in that server technology.

That is not to downplay the importance of skilled operators. One would be surprised by how much experience and technique go into opening a good ticket.

In short, and as a reality check, your on-call rotation will need more people in near linear proportion to the number of services in the product architecture.

|

|---|

| System administrators may be hard-pressed to rebuild their IaaS and PaaS practices to host the same level and diversity of services found in a typical Cloud provider. And it may not necessarily cost less. |

Conclusion

Leaving the Cloud is, at the same time, a financial and a technical decision. Spare capacity on-premises only accounts for the financial aspect, whether in terms of people or hardware.

Consider immediate cost savings before any move, such as using different allocation methods for the same resources and leveraging auto-scaling features whenever possible. For Kubernetes shops, cluster-autoscaling and Knative combinations pair up quite effectively to reduce capacity waste.

Above all, consider the total cost of the move, not only hardware costs. Sometimes using even more cloud services may reduce the system’s total cost of ownership, addressing many of the following concerns:

-

System architects may need to find alternatives for Cloud-only services. That takes time away from evolving the product.

-

Developers may need to roll up their sleeves and code some of those alternatives. That takes time away from building new features.

-

Operations teams may need to staff up and create entirely new procedures (manual or automated.) That is likely a gargantuan effort.

-

On-call schedules may need to be bolstered with extra people to account for an increased variety and complexity of page-outs. This one item should prove the most difficult to overcome.

I am curious about the math (and architectural results) behind this type of migration, and there are few formal studies on this point.