Balancing Capacity and Cost for Kubernetes Clusters

Infinite Choices, but Which Is the Right One?

Many services may become unused and forgotten in some corner of your Cloud provider bill.

Not Kubernetes.

Kubernetes hides its resource waste in plain sight, under a cloak of abstracted layers and compartments. From physical limits tracing their lineage to the early 1900s to a dizzying array of resource allocation techniques, it is virtually impossible for understand all nuances of how workloads are distributed across the environment.

In IT, there are three ways of dealing with problems in things we don’t understand:

- Learn more about those things. Learning more is the theme of this article. The article does not cover everything, but it addresses the most common blind spots. Knowing what to avoid and why also helps one focus one’s observations about the system.

- Reboot it. Whether restarting a pod, draining a node, or restarting a compute instance, “reboot it” is the Cargo Cult variation of resource allocation. In Kubernetes, this type of solution is often an illusion: a pod causing problems on a node will cause the same problems in its new hosting node.

- Increase capacity. There are classes of problems that may require more capacity, but many other problems that just happen to be resolved with more capacity. For example, suppose a pod with an undeclared memory utilization of 32 GB keeps crashing the nodes on which the pod is scheduled. A system administrator unaware of the Kubernetes resource allocation model may decide to reallocate the entire node pool with an extra 32GB for each node.

While the “reboot” solution is simply a time-wasting distraction, the guesswork in resource allocation is an insidious shortcut, promoting thoughtless waste to a system requirement.

Kubernetes Waste is Structural

Virtualization systems in production systems rely on workload owners specifying how many resources they may need.

Once again, Kubernetes is unique in that regard.

In Kubernetes, resource owners must specify the minimum resources they need (resource requests) and the maximum they can possibly use (resource limits.) And that is before we even start talking about affinity between pods and nodes.

Lost in that confusing mix, people tend to over-allocate resources to shield their workloads from resource starvation.

It is not unusual for a Kubernetes cluster to run with an allocated capacity several times larger than the workload usage within the cluster.

But how to avoid over-allocation?

-

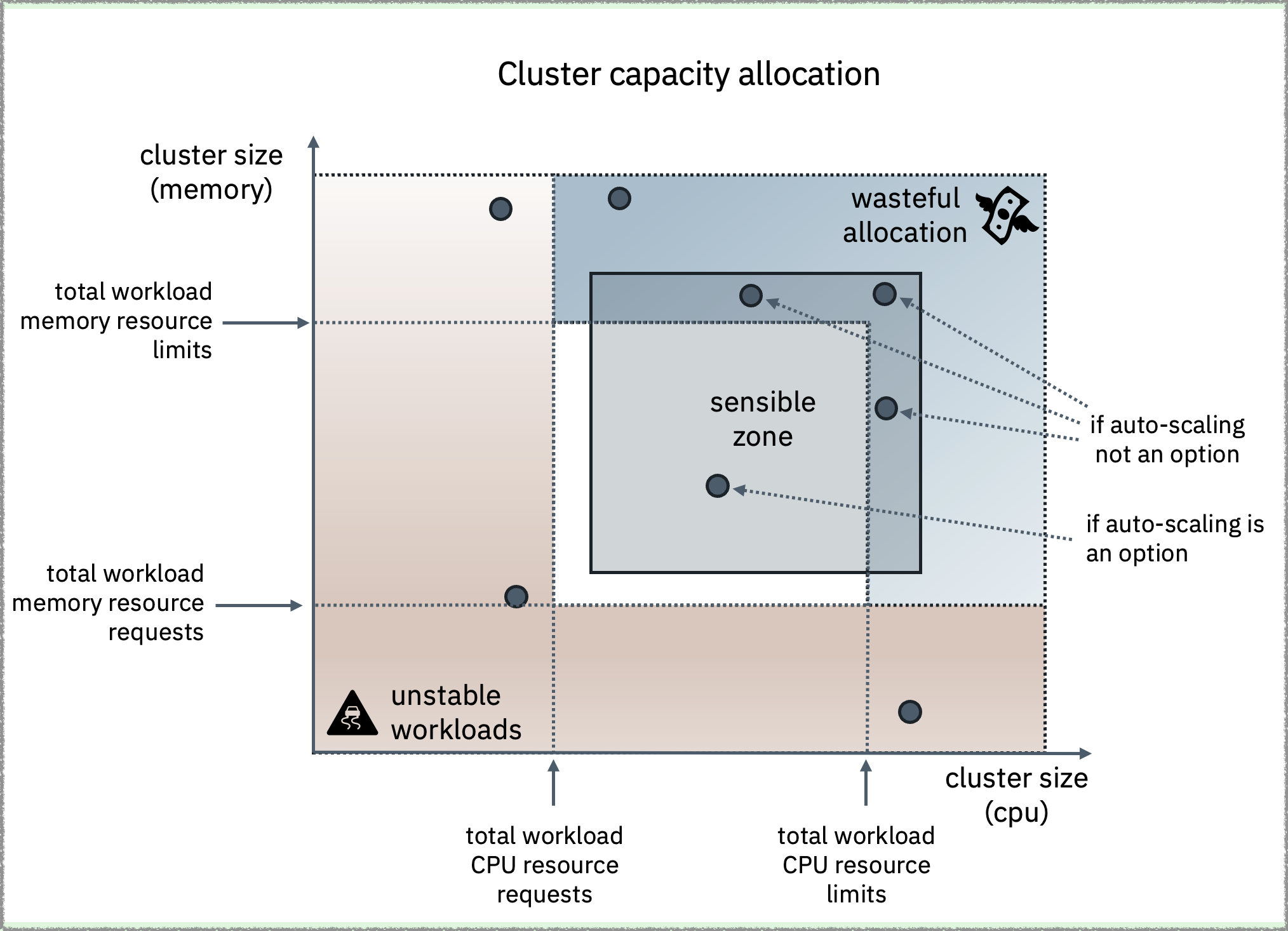

Should you set cluster capacity a few percent above the workload resource requests and hope that the capacity buffer is enough to handle eventual spikes?

-

Should we set cluster capacity to meet the sum of resource limits for all workloads and watch the bulk of your IT budget being spent on pre-allocated capacity?

|

|---|

| Figure 1 - The “sensible zone” for a Kubernetes cluster is where the overall cluster capacity is sufficient to meet the minimum requirements for all workloads, with enough spare capacity to deal with eventual spikes in demand. If fixed capacity is required, the cluster capacity should be set slightly above the combined limits of all workloads. |

Indeed, we can auto-scale everything to try and allocate capacity on demand. At the top of the auto-scaling hierarchy, cluster auto-scaling takes care of running the minimum number of nodes, but there is still the question of individual node capacity.

The compute instances underneath those nodes come in pre-packaged sizes with fixed ratios between CPU and memory. Dynamically creating a new node with the wrong size is better than always running that same node, but it is still wasteful.

System administrators must find the ideal node size capable of running all workloads while avoiding surprises such as Cloud provider bills going up instead of down.

Avoiding those surprises requires a keen sense of where the typical blind spots lie, which brings us to the following sections.

Blind Spot #1. Limits Are Often Hidden, Rarely Abstracted

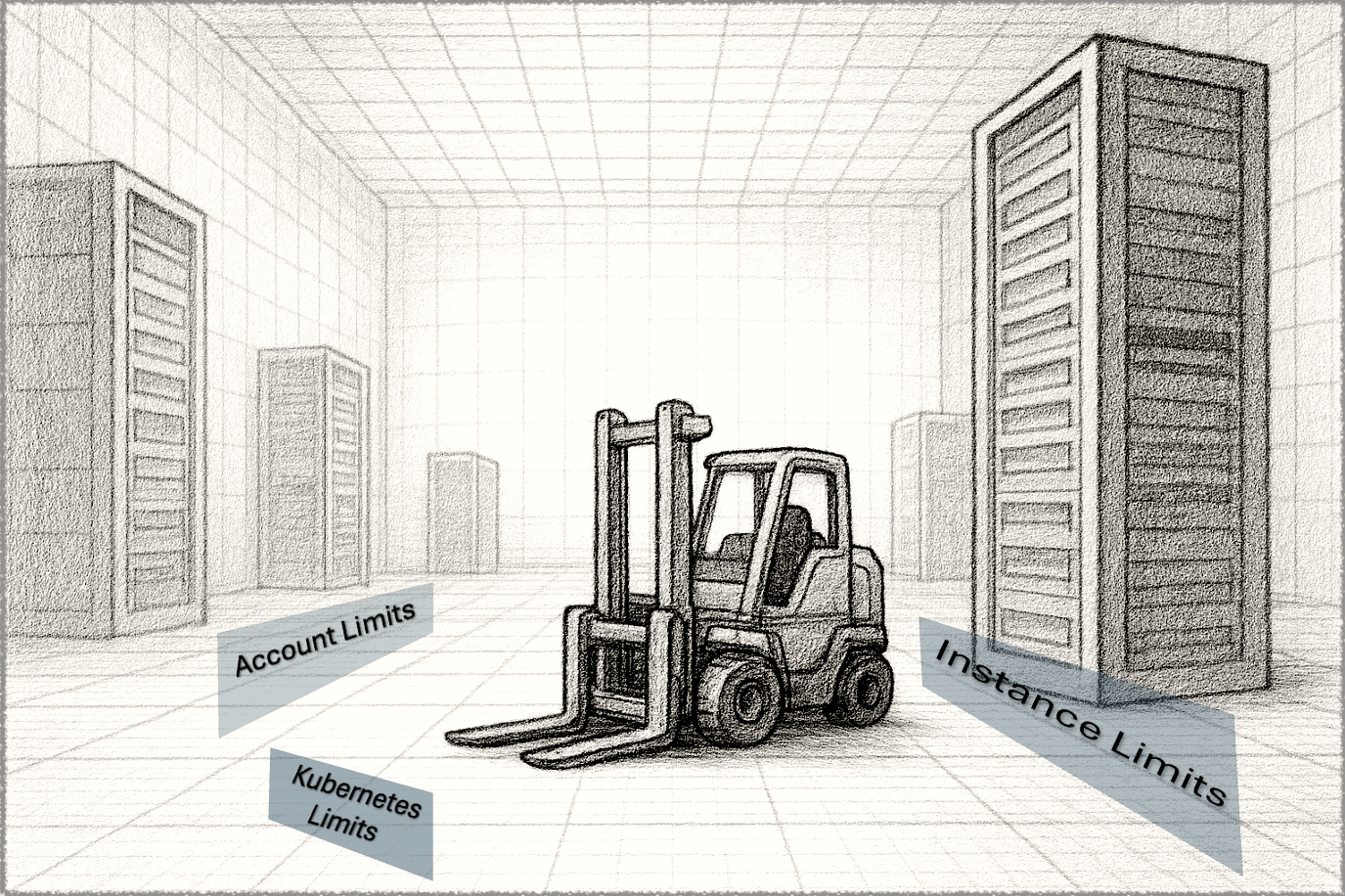

A running Kubernetes cluster sits atop a tall software and hardware stack, with each layer having its own capacity constraints and limits.

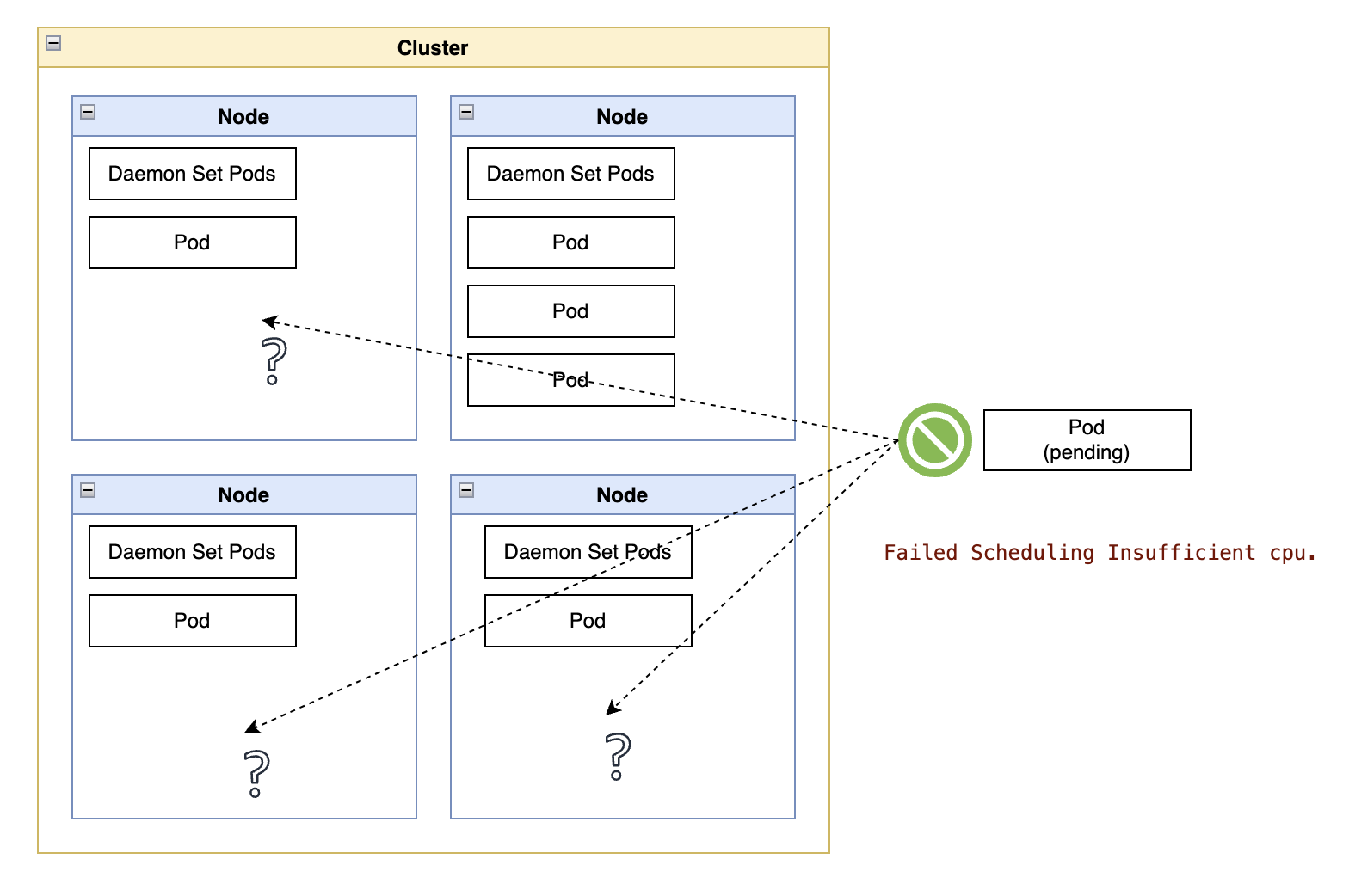

Limits lurking deep in that stack are a perennial source of seemingly mysterious messages indicating that pods cannot be scheduled on a lightly loaded node.

Those limits can be set at the operating system or the hardware level. As a software example, the operating system running a cluster node may have a maximum number of processes that can be concurrently open. For a hardware example, there may be a fixed number of PCIe slots in the computing device, which limits the number of storage volumes that can be mounted to a compute instance.

Few people will know all limits, but anyone managing Kubernetes clusters for a living should be familiar with these three:

-

Kubernetes limits. Kubernetes distributions have limits such as the maximum number of pods per node or the maximum number of nodes per cluster. Additionally, these limits are often different than those listed in the opensource documentation, such as those for ROSA Limits and Scalability

-

Compute Instance limits. Kubernetes nodes are compute instances with an operating system and various processes layered on top. A task as simple as requesting a persistent volume in Kubernetes may bounce into compute instance limits for how many storage volumes can be attached to the instance.

-

Infrastructure/account constraints. Cloud environments are virtually infinite in terms of capacity, but there are account-level limits that crop up when you least expect them. For example, you may not have problems creating the first few dozen clusters in your account. Then, the next request may fail because the cluster may need a new network gateway, and some cloud providers impose account limits on those1.

Takeaway: Read through your cloud provider documents about the limits in these three abstraction layers (Kubernetes, compute instance, and IaaS account.)

Blind Spot #2: Burstable and BestEffort workloads

Planning is only as good as the quality of the data going into the planning.

You cannot decide on the best size for compute instances when you don’t know how much the workloads will need.

Containers inside a pod may have any combination of resource requests and limits, with different combinations of CPU and memory reservations defining the quality of service for the parent pod as follows:

- Every container in the pod has both resource request and limit set, and for each container, request and limit have the same value: Guaranteed.

- Resource request or limit not set in at least one of the containers in the pod: BestEffort.

- All other pods not in the two previous buckets: Burstable.

BestEffort and Burstable pods do not tell the cluster exactly how much CPU and memory they plan on using. In some cases, it may be a minor omission, such as not specifying CPU limits. Still, in other cases it may be a cluster-wrecking omission, such as not specifying memory requests.

Below is my scale of minor to significant ommissions in how workloads declare their resource needs, starting with the most severe:

- No memory requests

- No memory limits

- No CPU requests

- No ephemeral storage requests

- No CPU limits

- No ephemeral storage limits

There may be some debate at the bottom of the list, but not at the top.

In the worst case, workloads without any memory declaration (resources or limits) may crash several nodes in rapid succession, so you need to be at least aware of their existence.

There are many open-source and commercial tools that can analyze the historical resource usage of workloads in a cluster. These tools can identify workloads that may be underperforming due to a lack of resources and, more importantly, those that can destabilize other workloads.

For larger environments, some of these tools can continuously monitor resource utilization and create optimization plans for setting workload resource requests and limits. For smaller use cases, one can run a simple kubectl command like this or something more sophisticated, like Robusta’s Kubernetes Resource Recommender.

Regardless of your chosen tool, you must understand how Kubernetes resource management works and scales across all dimensions. I wrote a comprehensive primer on Kubernetes scaling technologies.

Takeaway: Always identify all your Burstable and BestEffort workloads, then decide how much risk you are willing to take. There is no point in discussing budgets or ideal cluster node sizes when a significant share of workloads can simply start using cluster resources without notice or an upper limit.

Blind Spot #3: Overcome by Daemons

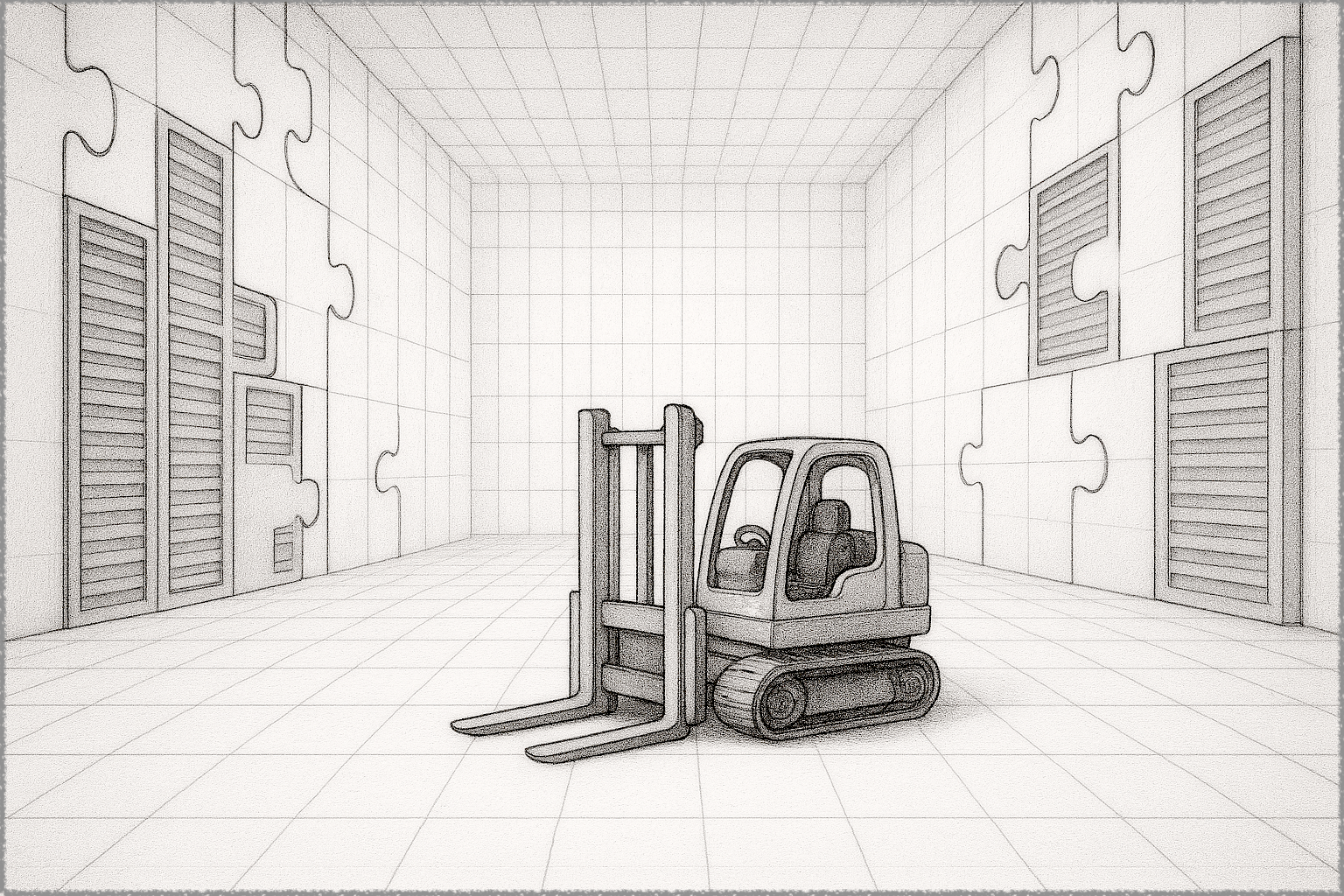

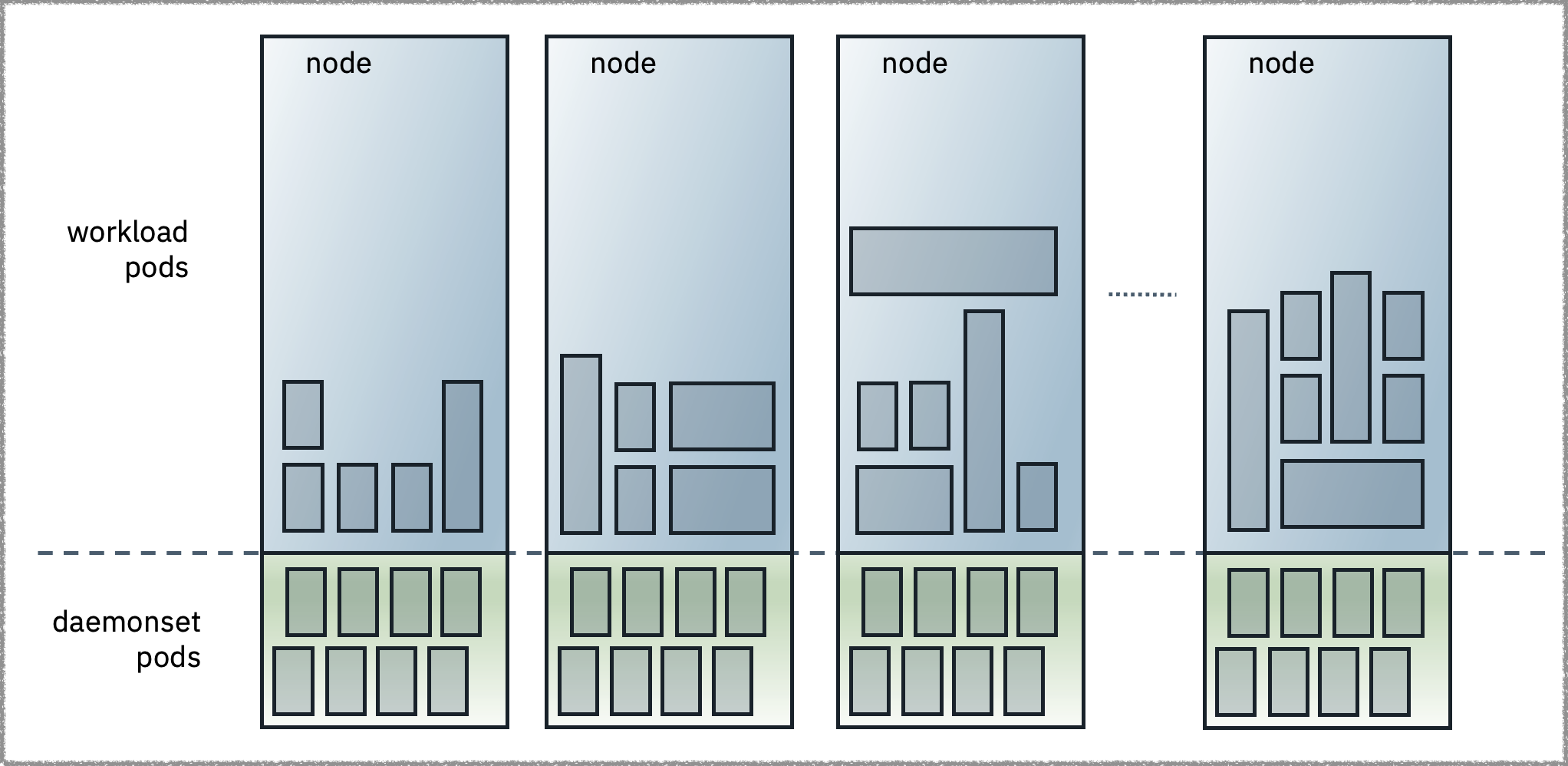

No matter the instance size, a fixed portion of the instance is reserved for the processes that make a node work within a larger Kubernetes cluster.

While those reservations can take up 1% or 2% of a node’s memory and CPU — somewhat more for storage — DaemonSets can take far more.

DaemonSets are typically used to run copies of pods on all (or some) nodes, augmenting the node capabilities with functions such as enforcement of security policies, log collection, observability, and storage.

A query to Prometheus, such as the one below, can show the memory resource requests for all DaemonSet pods across all nodes in a cluster - replace “memory” with “cpu” in the query to see memory requests:

sum by (node, daemonset) (

kube_pod_container_resource_requests{resource="memory"}

* on(pod) group_left(owner_name) kube_pod_owner{owner_kind="DaemonSet"}

)

These DaemonSets may get added gradually over time, and without asking the right questions about how many resources they will need, one can be blindsided by how little of each new node’s capacity remains usable by customer workloads.

“Figure 2 - DaemonSet workloads manage or extend the node capabilities. They consume fixed resources on a node regardless of customer workloads and effectively reduce the allocatable capacity of a node.” “Figure 2 - DaemonSet workloads manage or extend the node capabilities. They consume fixed resources on a node regardless of customer workloads and effectively reduce the allocatable capacity of a node.” |

|---|

| Figure 2 - DaemonSet workloads manage or extend the node capabilities. They consume fixed resources on a node regardless of customer workloads and effectively reduce the allocatable capacity of a node. |

Takeaway: Kubernetes DaemonSets can use considerable node capacity, especially when running on smaller compute instance sizes. Choose CPU and memory utilization thresholds for DaemonSets, then alert the operations team when that threshold is crossed.

Blind Spot #4: Bigger Instances, Bigger Root Volumes

While I argued in the previous section that smallish instance sizes can be wasteful, using larger instance sizes carries a different type of risk: storage limits.

As instance sizes increase, so does the number of pods per node.

Running more pods per node requires more disk activity, which brings us to the node root volume where that activity occurs. That root volume is where Kubernetes stores things like cached images and ephemeral volumes.

More pods mean higher demands in capacity, throughput, and transactions per second (IOPS). Of those three metrics, capacity is the easiest to exceed but also the easiest to observe — “disk full” messages have a way of making themselves known sooner rather than later. Throughput and IOPS tend to be the blind spots within the blind spot, with most shops not fully equipped to monitor or troubleshoot those problems.

So, if I double my instance size, should I double the capacity, throughput, and IOPS for root volumes?

In short, yes.

There is a word of caution here about whether your Kubernetes distribution exposes those settings to system administrators. For example, as of the writing of this article, ROSA allows the choice of disk size but does not allow the choice of throughput and IOPS reservations, so system administrators may have to locate the corresponding volumes in their AWS account to set those limits manually.

The last blindspot within the blindspot for this section is cost.

Cloud providers do not charge linearly for reservations. For example, AWS currently does not charge for volume reservations of up to 125 MB/s and 3000 IOPS when using general purpose volumes. However, if your larger compute instances require reservations above those free-of-charge limits, you will have new financial costs to consider.

Takeaway: Consider node root volumes’ three performance limits (capacity, throughput, and IOPS). Before choosing larger node sizes, you need to know whether you can increase those reservations and what their cost will be.

Blind Spot #5: Cheaper Instances, Fewer Volumes

Cloud providers do not optimize all compute instance sizes and families for containerized workloads. I often wonder if they even worry about instance sizes for Kubernetes.

As you choose larger instance sizes, the hardware limits in a typical server rack may become the limiting factor in the maximum size for those instances.

For example, as of the writing of this article, AWS EC2 has a limit of 28 volumes for its older instance generations regardless of instance size. As storage volumes are used to back persistent volumes, those 28 persistent volumes must be sufficient for the storage requirements from all pods scheduled in that node.

On the other hand, and still using AWS as an example, the more recent (and more expensive) instance series, such as 7 and 8, have volume limits that increase with instance size, making them more suitable for running Kubernetes workloads that require persistent volumes.

Takeaway: If your workloads require persistent volumes, read your cloud provider documentation and specs on storage limits. Then, assess whether your candidate instance types have enough “slots” for each node’s expected number of persistent volumes.

Blind Spot #6: Have You Talked to the Procurement People?

Technical folks (myself included) can be too quick to pull numbers from Cloud provider calculators and think we know what a compute instance costs.

For large companies, the real numbers are written in a contract negotiated for months between the company and the cloud provider. Those negotiated numbers are very different than those visible in external calculators.

The blind spot is that some of these discounted numbers may only apply to specific combinations of instance sizes and regions.

The rationale is that a cloud provider may be more willing to offer deeper discounts on a smallish 2x8 compute instance than a larger 64x256 instance. Those smaller instances can be more easily shoehorned in the unused crevices of a server blade on a rack - where they would go unused - while the larger instance may require an entire server blade.

Another related blind spot is that some discounted prices involve savings plans that require fixed reservation (or even prepayment) of capacity over a long period - months or years. Reducing wasted capacity reservation for your Kubernetes clusters may send account-wide utilization below that fixed reservation. Without a contract renegotiation on the minimum utilization, there may be no reductions in your Cloud provider bill.

Regardless of specifics about the discounted prices in that contract, initiating a contractual change before the contract ends is the equivalent of entertaining a new move right after unpacking the last box in your new house or apartment.

Takeaway: Before making capacity allocation decisions for your fleet of Kubernetes clusters, ensure you understand the actual cost of your options. You don’t want to find out your next cloud bill went up after you spent considerable resources resizing all node pools in the fleet.

Summary

Reducing the total operation cost for a fleet of Kubernetes clusters is an optimization problem in a constrained space.

As with all math optimization problems, one must know their objective functions, decision variables, and constraints.

In plain English, one must know what happens to costs when the system settings change and which changes lead to unwanted results.

If individual nodes have the “wrong” resource allocation for the cluster workloads, even the best node auto-scaler algorithms and resource optimization tooling can only do so much.

Meeting workload objectives is the primary goal, but the total cost of ownership cuts directly into profits, so always consider instance pricing when making decisions. Depending on the workload, something like a dedicated pool of spot instances can be a sensible solution at a fraction of the cost.

And finally, aim for continuous improvements rather than ideal allocation. Simple changes can achieve considerable gains, while other optimizations may require more extensive performance analysis and reassessment of reservations at the workload level.

Footnotes

- Sometimes, soft limits are set to avoid runaway resource allocation, and your cloud administrator can quickly increase them. Sometimes, hard limits require escalation or redesigning the entire system.