The Conflicted Economics of Prompt Engineering in Software Development

“If you are nothing without this suit, then you shouldn’t have it.” - Tony Stark

With prompt engineering entering the professional vocabulary and the arrival of foundation models trained in programming languages, software engineers did not take long to look into prompt-assisted code generation.

As a software engineer with well-rounded experience in architecture, design, operations, and programming, I can see cause for enthusiasm for applying AI in software development - something I will cover in a follow-up story.

However, positive economics depend on how much effort I need to put into that explanation and the quality of the resulting answer.

Some problems are localized to small tasks; they are simple to describe and have trivial solutions. Their resolution is covered in training models to the point of overfitting.

Other issues involve complex relationships to different parts of the system, are hard to recognize, and their solutions include trade-offs that evoke explanations starting with “it depends.”

For those problems, anecdotal evidence reveals AI hallucination and failure rates that, produced by humans, would evoke the words “human resources,” “performance improvement plan,” or even “urine test.”

Since the story got impossibly long, I split it into two parts:

- Part 1 (this story): The economics of writing code. Here, I look at the short and long-term economics of solving non-trivial software engineering problems, using a real-world case study to compare the performance of a generative AI code assistant against the traditional, unassisted method.

- Part 2: The economics of creating and operating large systems. In this story, I will cover why we are missing out by focusing AI training efforts on coding assistance (where humans already excel) instead of the natural language surrounding the technical aspects of creating and operating an entire system.

Training for the Hard Problems

The principle of training AI on complex problems is still the same: show the AI enough examples to infer patterns and predict outcomes for situations similar to those where the data was collected.

When a programmer asks for a “Python function that reads the contents of a URL” to an AI model trained on 159 gigabytes of Python code source from 54 million GitHub repositories, we know a nearly identical solution is in that training set, right next to comments that are an almost perfect match to the wording of that request.

If that abundance of training material was not enough, the training data also contains many public-domain articles covering basic topics, in no small part because they are easier to write and consume.

But what happens when you work on a programming language that is not one of the most used programming languages in the world or use combinations of components glued together with bespoke, confidential source code written inside your organization?

In those situations, there is certainly less material to train the AI, introducing gaps in the training data and, consequently, reduced quality in prompt results - I will illustrate that point with a case study in the following section. Additionally, when dealing with copyrighted or access-controlled source code, some content may have to be left outside the training data, further increasing the gaps in domain coverage and decreasing the quality of the answers.

This is the point in the discussion where someone raises their hand and asks:

Have you tried tuning a foundation model?

Yes, fine-tuning a foundation model is a popular solution to adapting a trained AI model to the distinct characteristics of a specific training set. Fine-tuning a model, an activity where you start from a larger AI model and show it examples that are closer to the ones in your organization, costs a tiny fraction - think thousandths - of the cost of training a model from scratch.

Spending a tiny fraction of the cost while getting better results sounds like great economics, but keep in mind the starting point for those savings is in the realm of tens of millions of dollars and growing 4-5x every year.

That bargain price tag may still run in thousands of dollars per month in compute-costs alone.

“Non-sense. I can use a local LLM and train it on a couple of GPUs I bought on eBay and get the whole thing done for the price of a good dinner.”

The first part of the rebuttal is true - you can train or fine-tune a local LLM - but it is that second part that separates an inconsequential weekend project from actual software engineering.

The economics of fine-tuning a public foundation model are terrible.

Going from a prototype to a hosted solution can take as much as 27 times the effort spent on the prototype. Once that prototype is done, you have to factor in hosting costs, where you either rent compute power from a cloud provider or host your own hardware, then contend with the reality that fine-tuning is a means of improving the language portion of the model but not so much a way of adding knowledge to the final system.

After all, not even all examples in the world fully cover every possible function signature or CLI command, so you have to look at RAG patterns (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) to inject that knowledge into each prompt, which in turn means you will need a database, a query engine, and some time fine-tuning those augmentations to each prompt sent to the AI model.

And if you are serious about using that fine-tuned model augmented with a RAG system, you will need to develop a Machine Learning Pipeline around that solution. While designing that pipeline, you must decide on metrics to track the model performance, methods to collect those metrics, create processes for responding to feedback, and more processes for rolling out updates.

If that is not enough, you may also need to experiment with alternative fine-tuning methods to decide on the best approach for your effort.

The economics of muscling through that entire effort are those of a research project, with heavy upskilling on new technology and the added engineering effort of building and operating the final solution. And to cap the entire argument against the economics of training a localized model, there is always a chance the next version of that same starting foundation model will outperform your entire investment.

Assuming you are convinced that rolling out and operating your own model at the small scale of localized deployment is a lousy business, let’s look at a real example of using a code-generation assistant based on public foundation models - I used three different AIs throughout the exercise to ensure the results were consistent.

Case Study: Single Sign-On Configuration

This section is based on a recent real example where I had to package two components of a more extensive solution for an air-gapped environment (no direct connection to the Internet for security and regulatory purposes.)

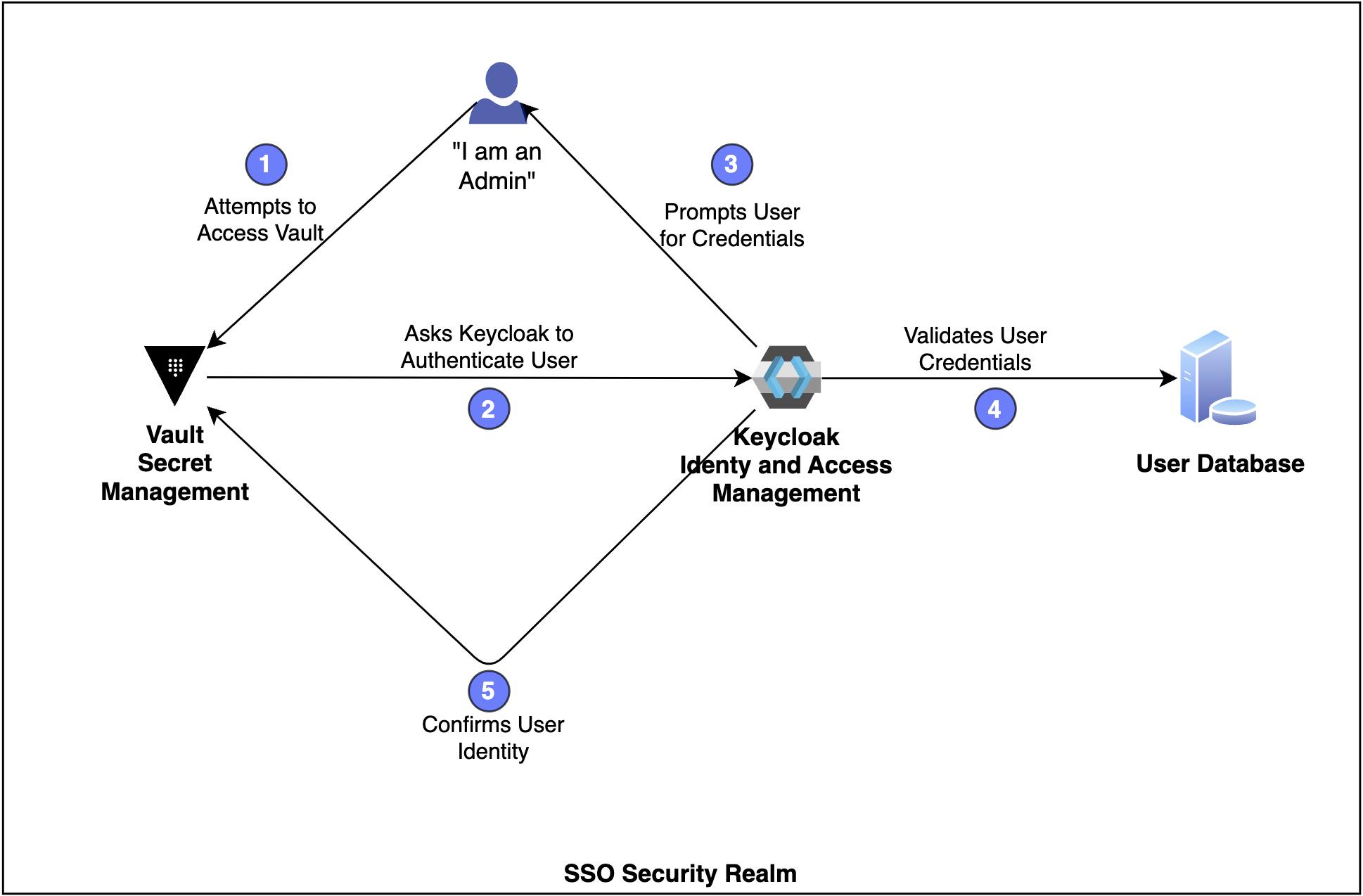

I needed to configure an instance of HashiCorp Vault on a Kubernetes cluster to secure logins using an OIDC Client hosted on Keycloak. If you are not very technical, HashiCorp Vault is a service for managing secrets, and Keycloak is a service for managing access to other systems. In this solution, we want to use Keycloak to authorize who can access the secrets on Vault.

As a “hard problem,” this integration has a programming element combined with packaging and configuration aspects.

Securing access to Vault with an external access manager is not a rare system combination, but Vault can work with a dozen different authentication tools, including the public hosted offerings from the largest Cloud providers, so there is considerably less public content about using Keycloak than for those other alternatives.

When working on such a problem, I loosely follow the following steps, a framework I will later use to evaluate the AI’s performance.

- Look for the documentation for both products.

- Locate APIs and command-line interfaces.

- Read through functions and parameters.

- Map functions and parameters to the larger problem.

- Draft an initial solution on a notepad (or blank page in a code editor.)

- Iterate over the draft side-by-side with documentation.

- Create a program to automate the instructions.

- Write the documentation or notes for the component.

- If I consider the solution generally usable, write a public blog or technote.

Phew! That seems like a lot of work, right? Time to ask an AI:

How do I configure Keycloak OIDC as an authentication method for HashiCorp Vault? Provide reference URLs after you give me the instructions.

The AI printed two pages worth of instructions, which were helpful and landed me in the middle of step 5 (draft an initial solution.)

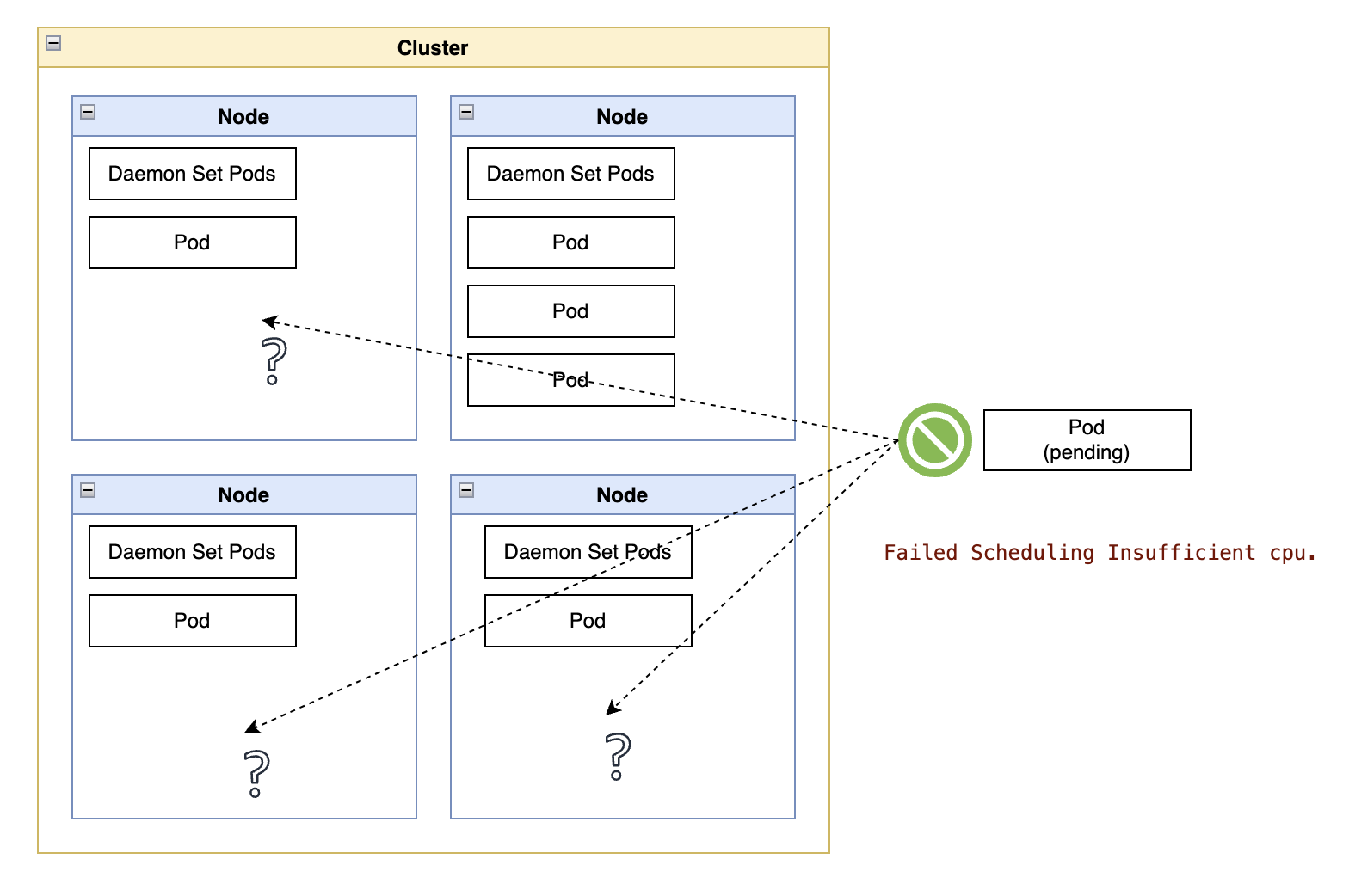

Attempts to use the solution as drafted failed for several reasons, which is expected at that stage. However, unexpected issues forced me to backtrack to the earlier steps in the process.

The first problem was Vault complaining about not trusting the custom certificate in the URL for the Keycloak OIDC discovery endpoint.

I modified the initial prompt to indicate the Keycloak server used a custom certificate. Still, the AI seemingly ignored the alteration and did not produce any change in the responses. Assuming further clarifications would be equally ignored, I prompted the AI directly about how it would address the error message. The AI redeemed itself by showing an updated command with the correct parameter.

Next, while validating the solution and finally logging into Vault with a user stored in Keycloak, I noticed the Vault UI showing a numeric identifier for the user instead of the user’s email or full name. More than being friendlier to users, a recognizable name is also an extra layer of security in case the user has access to multiple accounts with different privileges (common in system operations.)

One could debate the importance of making that change, but I explained the problem in plain text to the AI, hoping for a solution. The AI generated another update for one of the commands, which did not produce the results I requested. At that point, I reverted to my usual step-by-step system and read through the command parameters.

The failed solution was because the parameter offered by the AI (“oidc_claim_mappings”) did not exist. The correct parameter name should be “claim_mappings”. Pause to note that while one would expect the Vault command-line interface to complain about the non-existent parameter, it did not.

At that stage, whatever time I had gained skipping the first four steps before drafting the initial solution was lost, and then some. As the joke goes: “One hour of debugging can save you five minutes of reading the documentation.”

I iterated over the draft following the documentation (“step 6”) and reverted to asking for the AI’s assistance with step 7 (“create a program to automate the instructions.”)

In that step, I asked the AI to generate a shell script automating the steps related to Keycloak, and it produced a respectable series of shell script commands based on low-level utilities such as “curl” and “jq.” On the less respectable side, the AI hardcoded all URLs and placeholders for credentials in the script, which would be terrible form for a human.

There was, however, a more severe and less visible problem: Keycloak already has an administrative CLI. Using direct access to REST endpoints with “curl” and processing JSON responses with “jq” worked but resulted in code that not only was harder to read (and maintain) but would also be sensitive to any future changes to the product APIs.

From an economics perspective, this module would have to be rewritten and retested when people discovered the glaring mistake, which would probably coincide with the first API change in Keycloak. There would also be reputational consequences (for me) in missing the existence of an entire administrative CLI while writing the code.

I played along with AI, not calling out the existence of that CLI. Curiously, the AI eventually switched its implementation strategy and offered a solution using the appropriate CLI without acknowledging it had been suggesting an incorrect approach in the preceding prompts.

With all the running bits completed, the AI’s assistance in step 8 (writing the documentation) impressed me the most.

I used the following prompt:

Write the step-by-step instructions for the following problem, grouping the information in sections titled “Overview,” “Prerequisites,” “Steps,” “Validation,” “Troubleshooting,” and “References.”

I want the result in markdown format that I can use on a README.md file.

On each step, add a “Command reference” link to the original documentation page describing the commands.

Here is the problem:

How do I configure Keycloak as an authentication method for HashiCorp Vault?

My Keycloak server is running on https://keycloak.server.com, using a custom certificate. The Realm name is “example”.

The Vault server is running on https://vault.server.com

I received an almost complete technical article in response. It had issues like a prerequisite section missing references to the product documentation pages and the same hallucinations seen in earlier steps. However, the AI assist addressed a common pain point for me and many other software developers: writing documentation at the end of a creative session, where the brain is wired to create solutions and not so much to explain the final solution - oh, and tired, too.

You can read the (lightly edited) version of the response. In full disclosure, I had to fix several bits of markdown for the URL links, but that only took a couple of minutes.

AI or Traditional Method. Who Won?

In this section, I break down each step in my usual process, calling out a “win” for the AI or “human method” in each step and then adding some commentary about each conclusion.

Step 1. Look up the documentation for both products

Win: AI

The AI gave me a usable link for each part of the process, embedded in the instructions, and with less friction than running a web search.

Web searches surfaced helpful blog entries and Stack Overflow links, but I had to vet through several entries (and ads), open the pages to skim through them, and then click a few links in the product websites to find the document sections I needed.

It is worth noting the traditional process has advantages in the long run - I’ll come to them later - but I am looking strictly at time spent and immediate results.

Step 2. Locate APIs and command-line interfaces

Win: AI

Similar to the previous step, asking for links in the context of the actual problem produced good results, with the advantage of having them embedded in the instructions close to the steps where the APIs and CLIs were being used.

I had to spend extra time writing down the problem for the AI than I would typically spend writing my search criteria, but that was not extra time relative to the entire activity.

Step 3. Read through functions and parameters

Win: Human Method

Reading manuals and understanding the technologies involved in the problem is a fundamental aspect of producing a workable solution with the lowest cost of ownership in the long run.

AI drafts may be acceptable on a disposable prototype but inexcusable on an actual product. The AI cannot create a semantic network of the product documentation in our brains or its own circuits, as evidenced by the hallucination of the “oidc_claims_mapping” parameter or the temporary blindspot surrounding the Keycloak administrative CLI.

Step 4. Map functions and parameters to the problem

Win: Human method

The AI drafts surfaced some parameters in the drafted solution, but those parameters were only a fraction of the whole. Reading through the documentation gave me a much better perspective on assessing the quality of the original AI draft and other alternatives and considerations for adapting the solution to a production system.

Understanding the overall range of configurations in the underlying technologies is the only way to judge whether the solution will be stable and have the lowest cost of operations in a production system.

Step 5. Draft a solution on a notepad (or blank code editor page)

Win: AI

After all iterations, the initial draft contained 90% of the final solution, an outstanding effort from a single-sentence prompt.

Using the traditional method of looking up examples through web searches would surface all the building blocks required to create such draft. Still, the AI could string them together much faster and generate what was basically a technical article with steps to solve the problem.

Step 6. Iterate over the draft side-by-side with documentation

Win: Human Method

I took over from the AI and did the iterations, partially because it could not improve upon its (admittedly solid) first draft but mainly because I lost trust in the AI’s accuracy after troubleshooting the hallucinated parameter for the Vault CLI and the scare with the temporary blindspot with the Keycloak CLI.

This experience matches what I heard and read from other senior engineers about how AI chats tend to plateau and even derail once you start to add more details about your request.

Step 7. Create a program to automate the instructions

Win: Human Method

Setting aside the initial AI blunder of ignoring the Keycloak administrative CLI, I liked how the AI was able to create a shell scripting boilerplate using the “getopt” command.

However, writing over a copy of an existing shell script in our project would have been more efficient due to their fit to our coding standards (such as copyright statements, naming conventions, message formatting, error handling, and others.)

Step 8. Write down the final instructions in a markdown file

Win: AI

The original write-up in step “5” felt like the skeleton of a technical article.

It is worth noting the AI had difficulty honoring my request to write the output in markdown format, switching back mid-text to its rich-text rendering format, no matter how specific I tried to be about the entire output using the markdown format.

Also, the AI “plateaued” in improving the quality of answers against refined prompts, such as ignoring my different wordings of a request to embed links to the product documentation in the prerequisite section.

Those issues were, however, minor relative to the overall content.

As long as one understands they should not spend too much time trying to keep refining prompts in an attempt to get the final version of the instructions, the AI saves time relative to starting from a blank page.

Step 9. Write a public blog or technote.

Did not attempt

I think the solution may be of general interest - for an admittedly niche audience - but I simply did not have the time. If I did have the time, I would still prefer to write it myself with the editorial assistance of an AI rather than defer the writing to the AI entirely.

With AIs able to write technical articles on the fly, I cannot imagine anyone willing to read through the result of someone else’s prompt rather than prompting an AI to write something bespoke to their particular problem.

The Short-Term (potential) Gains Are Appealing

In the short term, with four wins for each side and some loose counting of the overall time spent in the activity, I declared a tie on the economics of enlisting a generative coding AI to my workflow.

Different case studies with different technologies may swing the balance towards net gains or losses, depending on how well the training data covers the domain.

My exercise used a somewhat well-established product - Keycloak is a CNCF incubation project - and the de-facto standard for secrets management, so I am assuming good, if not extensive, coverage in the training data.

The AI initially missed a severe blindspot and hallucinated a few parameters. However, it made up for its mistakes in the natural language areas of identifying useful documents and writing documentation drafts.

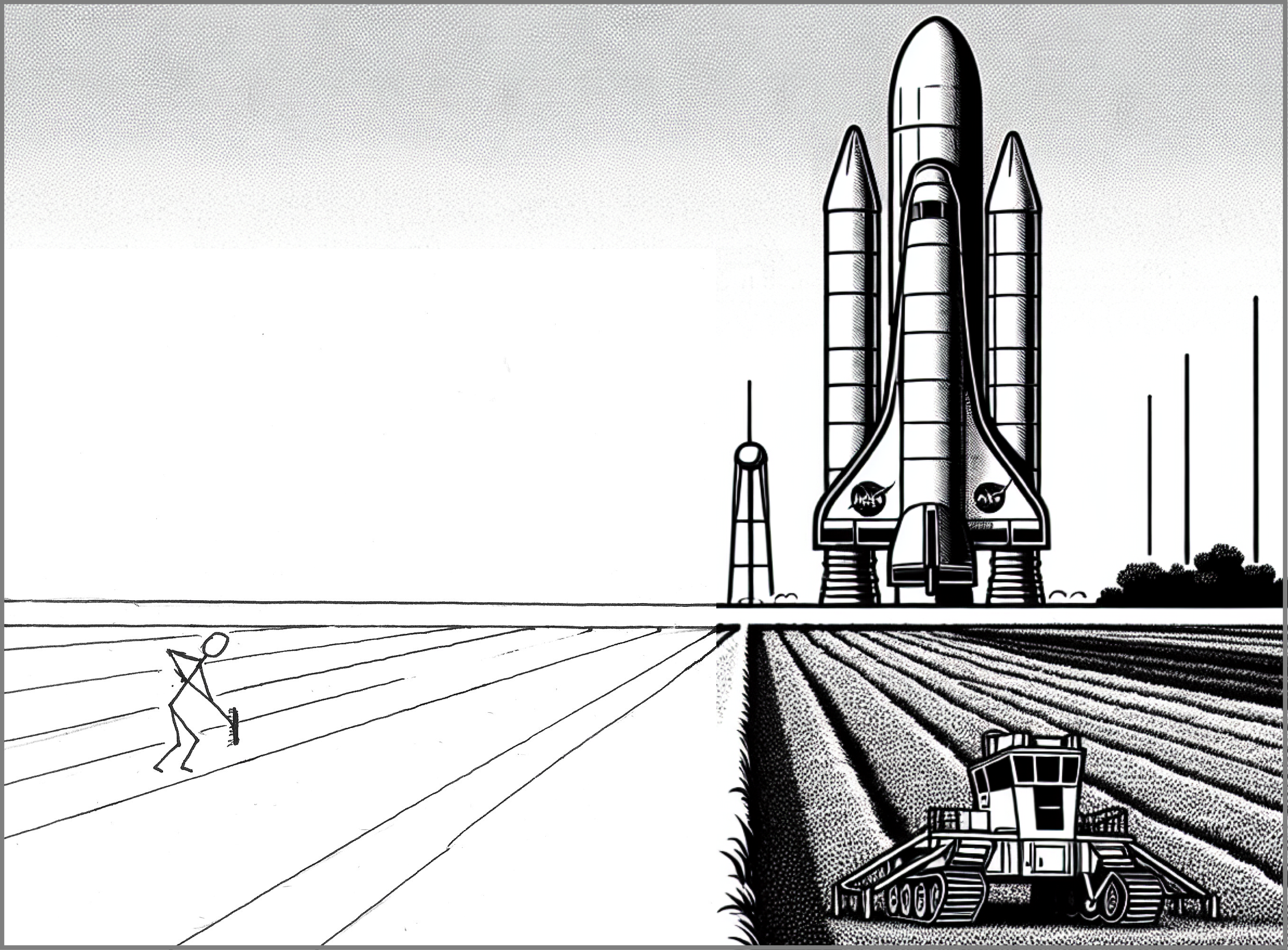

Outside this assessment, the AI also routinely excels in the initial drafts for the short Python-based functions I tend to use in side tasks, such as analyzing the contents of our Git repositories, typically requiring only a few editorial changes.

I think focusing the tool’s usage on ancillary, simple tasks is the sweet spot for AI assistants. However, my enthusiasm for it is more of the incremental type - such as when I first mastered a data pivot in Excel - than the kind where I would consider quitting my job and starting a software company staffed with inexpensive robot developers.

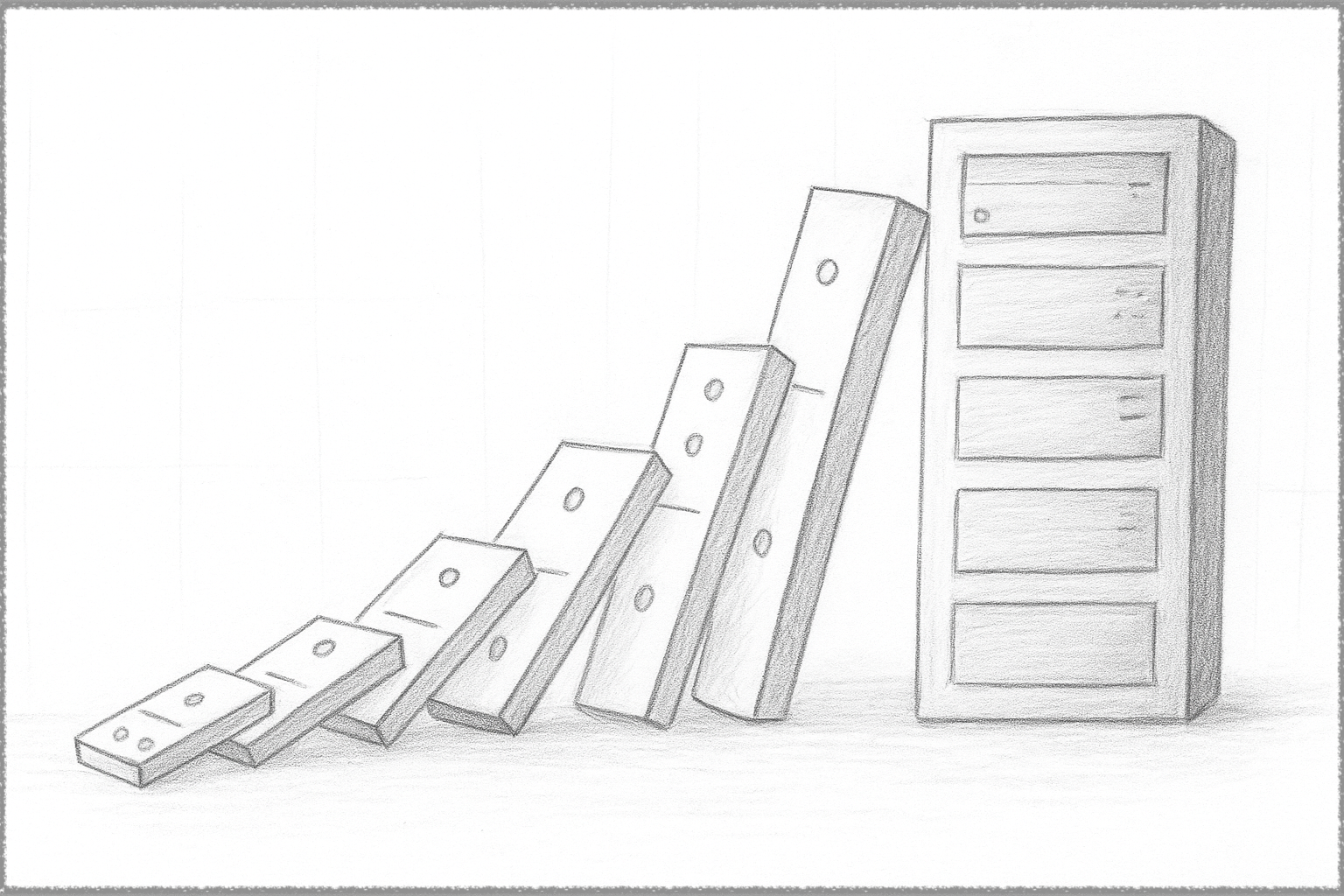

The Long-Term Losses Are Devastating

In the long term, the entire debate about the gains and losses of prompt-based programming ignores a crucial byproduct of the problem-solving cycle: gaining knowledge.

There is a formative aspect in solving problems using traditional methods of investigation, discovery, abstraction, programming solutions, and validating the resulting code.

While investigating the building blocks for a solution, we are creating an entire domain model of those concepts, full of boundaries and trade-offs between things that work well under different circumstances.

Receiving an answer to a question will never make our brains tread the same steps of processing and assembling the building blocks of that answer. In that sense, quicker results committed to a code repository come at the expense of not building skills and maturing talent at the same pace.

That is a frightening trade-off backed by ambitious assumptions that AI capabilities grow faster than we erode ours.

For how long will use cases ending in “make sure the results [of a prompt] are correct” still be valid in a system where asking for those results becomes the norm and we collectively atrophy the skills required to arrive at those same results?

Some technology enthusiasts make the case for generative AIs being a great learning tool. Still, I often hear those arguments from senior people learning yet another skill - backed by their substantial knowledge of multiple domains - rather than from those starting their careers.

Other rebuttals resort to a question turned argument: “Would you rather code in Assembly?”. Can people not see the distinction between adopting a higher abstraction language layer versus a cognitive process favoring interrogation over abstraction and reasoning?

There is also little acknowledgment that asking for help, a skill at the core of prompt-based coding, is an evolved skill in itself.

The general messaging may be of industrial revolution, but industrial revolutions unlock untapped resources, which is not the case here.

Generative AI, at its core, taps into existing resources already explored and consumed in different ways, relying on contentious mining of public-domain resources at the source and on use-cases cementing existing expertise at the point of delivery.

Along the way, the whole process endangers the early stages of the talent pipeline and threatens deskilling the very pool of content authors generating the raw material the AI depends on.

There has to be a better way.